Garry Watson had a lot to brag about. Considered one of Whistler’s founding fathers, he was instrumental in the eventual establishment of the ski resort and its renowned village, and, in innumerable other ways, lent a steady, guiding hand that ushered Whistler into the thriving ski destination it would become.

A lengthy list of accomplishments that could fill several lifetimes, no doubt. But Watson, who died earlier this month at 89, never did it for the plaudits.

“He was very humble. He didn’t blow his own horn. He did things quietly in the background,” recalled Anne Popma, Watson’s wife of 36 years. “Garry always had the bigger picture in mind, and that was the creation of a community, not just a strip mall and parking lot for a ski hill … They were charting new territory.”

That picture began to take shape for Watson in 1961, when, after climbing up to the top of Whistler Mountain (then called London Mountain), he peered down at the wild valley below, and made a decision: this is where he would live.

For most, this would have been where the pipe dream ended. But for Watson, an accomplished lawyer and tireless man of action, this pie-in-the-sky idea wasn’t so far-fetched.

“He just loved the valley. He loved the mountains, He loved everything about Whistler,” Popma said. “He spent a good part of his life making it what it is today.”

‘THE RIGHT THING TO DO’

As a member of the Garibaldi Olympic Development Association, Watson was a key player in selling Whistler in a 1968 Olympic bid, a precursor to the community realizing its own Olympic aspirations at the 2010 Games.

That dovetailed into the establishment of Garibaldi Lifts Ltd., which assessed the viability of London Mountain as a ski area years before the resort officially opened to skiers in the winter of ’66.

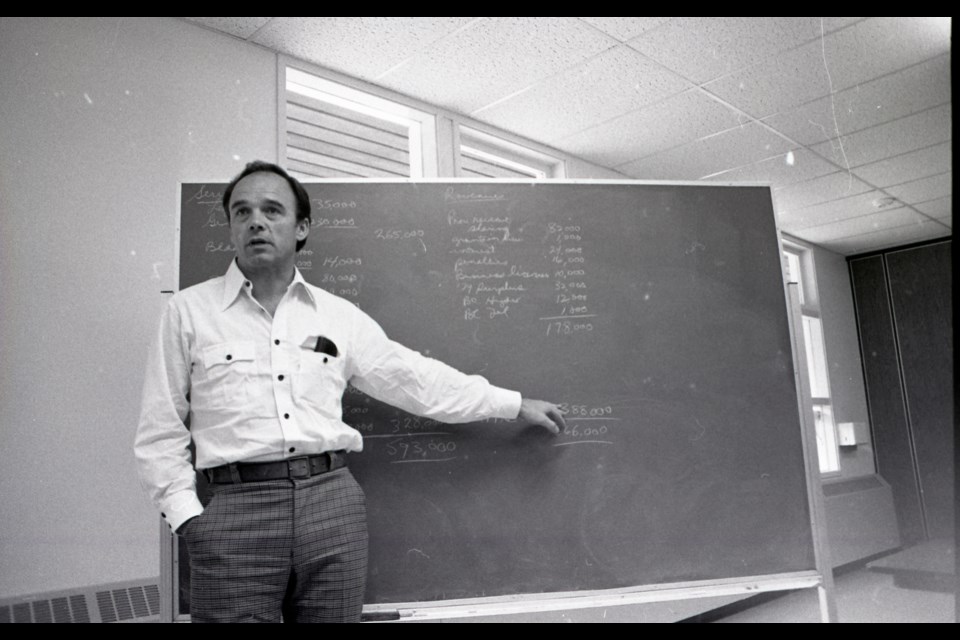

Watson also served on Whistler’s original council, elected in 1974, and was the point-man on negotiations with senior levels of government on the eventual establishment of Whistler as a resort municipality the following year.

“These guys were selling a dream at the provincial and federal level that you couldn’t do today. They were basically saying, ‘Look, we’re going to build a destination resort from scratch, it’s going to be developed under the management of the local town, and, oh by the way, we need a whole bunch of money,’” remembered Drew Meredith, Whistler Real Estate Co. founder.

Original Whistler councillor and current Sun Peaks Mayor Al Raine—whose own legacy looms large over the resort—considered Watson a trusted mentor, his legal acumen and practicality a fitting complement to Raine’s more heady ideas.

“We shared some common vision,” Raine said. “I had no understanding whatsoever how the political system worked. We had this vision we could build a tourist destination ski resort at Whistler and it would work, but with Garry’s legal background and development background, he had the ability to figure out how to do it. I was his student. I had lots of vision and big ideas, but none of the practical experience to make it happen.”

Selling their shared vision for a pedestrian-only village at the foot of Whistler and Blackcomb mountains proved to be a taller order than one might expect with the benefit of hindsight. Inspired by the walkable villages they had visited in European ski towns, Watson and Raine had to contend with a group of private landowners who wanted to see Whistler Village developed on their plot of land—for obvious financial gain. Hard to fathom today, it would have likely created a series of ski villages dotting the highway, as opposed to the consolidated village millions of visitors enjoy today.

“We went to numerous meetings in Victoria in the days when Whistler could have gone a completely different direction. Cabinet ministers in Victoria respected him. He had a great ability to present ideas and concepts and get his point across without talking for 10 minutes,” Raine said. “I’m sure most people in the community don’t understand the pivotal role that he played. He didn’t do it because he thought he was important or his ideas were important, he did it because he felt like that was what Whistler had to do. It was the right thing to do.”

‘BUILD IT, BUILD IT, BUILD IT’

It was this strong moral sense, along with a fervent love for Whistler that only seemed to grow deeper as time passed, that informed all the ways Watson gave back to his community. Along with serving three successive terms on council as alderman, he also served on the board of the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District, the Community Foundation of Whistler (now the Whistler Community Foundation), and the Whistler Health Care Foundation, a role in which he led fundraising efforts to acquire the Sea to Sky’s first-ever CT scanner at the Whistler Health Care Centre ahead of the 2010 Olympics.

“It was all these things that are essential to a healthy community,” Popma said.

Only the second person to be awarded the Freedom of the Municipality by the Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW), the highest order a council can bestow, after resort pioneer and historian Myrtle Philip, Watson set a formidable example for the dozens of elected leaders that would follow in his footsteps.

Whistler Mayor Jack Crompton said Watson was always available for advice, even in recent weeks, before his health took a turn.

“Garry was a mentor for people. I have had a lot of conversations over the last week about his work and one thing that jumps off the table is Al Raine saying how big of a mentor he was to him,” he said. “It strikes me that, when they started to work together in the early ’70s, he was mentoring people then, and weeks before he passed, he was mentoring me, consistently sharing ideas about how Whistler could be a better place. From 1961, when he first saw the valley, until he left us, he’s been working to build this place. It’s pretty exceptional.”

Asked for the most significant thing he learned from Watson’s guiding influence, Whistler’s mayor didn’t hesitate.

“The critical importance of investing in housing for workers. Garry had a lot to say about a lot of things, but he was a broken record on housing. Build it, build it, build it,” Crompton said.

By the late ’80s, Watson could foresee the incoming need for affordable housing locally. In 1989, he was hired by the RMOW as its employee housing coordinator, and was later appointed as the executive director of the Whistler Valley Housing Society—a precursor to the Whistler Housing Authority, started in 1997—and successfully launched land acquisitions and zoning applications for housing projects on Lorimer Ridge, Millar’s Ridge and in Brio. Watson was also instrumental in establishing the use of restricted covenants in the village, “ensuring village properties would always be available for public rental,” Crompton said. “And those are just a few of the concepts that he brought to the table. He had a special blend of vision for the future and legal training that allowed him to deliver that vision in important ways.”

FOR THE COMMUNITY

But beyond the many undeniable contributions he made to the community he so loved, Watson was at heart a playful, giving, and thoughtful man who told anyone who would listen that his greatest achievement was marrying his wife, Popma, who he met on a blind date in 1985.

“He was a fun-loving guy,” she said. “He loved to make people laugh, and he could tell stories to make them laugh. He was generous. He was kind. He made people feel good.”

Whistler’s journey from tiny ski-bum enclave to modern tourism mecca has been an unlikely one, to say the least, and that was not lost on Watson himself, who never missed an opportunity to marvel at the ski resort that he played a vital role in shaping.

“We would go to concerts in Olympic Plaza, and he would just look around and be so proud of what had happened here in Whistler,” Popma said. “The resort is almost secondary. Yes, we need a great resort, but it was the community that always motivated him.”

The RMOW is hosting a reception for Watson beginning with refreshments at 4 p.m. on May 2 at the Maury Young Arts Centre. Whistler Museum executive director Brad Nichols will lead a presentation detailing Watson’s legacy in the community during the council meeting, which begins at 5:30 p.m..