In Part 2 of our geological overview of Green Lake, we look at the dramatic effects of glaciation on the Coast Mountains, some modern geological settings around the lake, and how geology attracted the First Nations and European settlers to the area.

The landscape of Canada was profoundly changed by Ice Age glaciation, and Green Lake is a fabulous place to see the effects of this glaciation up close. About 16,000 years ago, a huge, two-to-three-kilometre-thick mass of ice called the Cordilleran ice sheet covered all of B.C., creating an environment more like modern-day Antarctica.

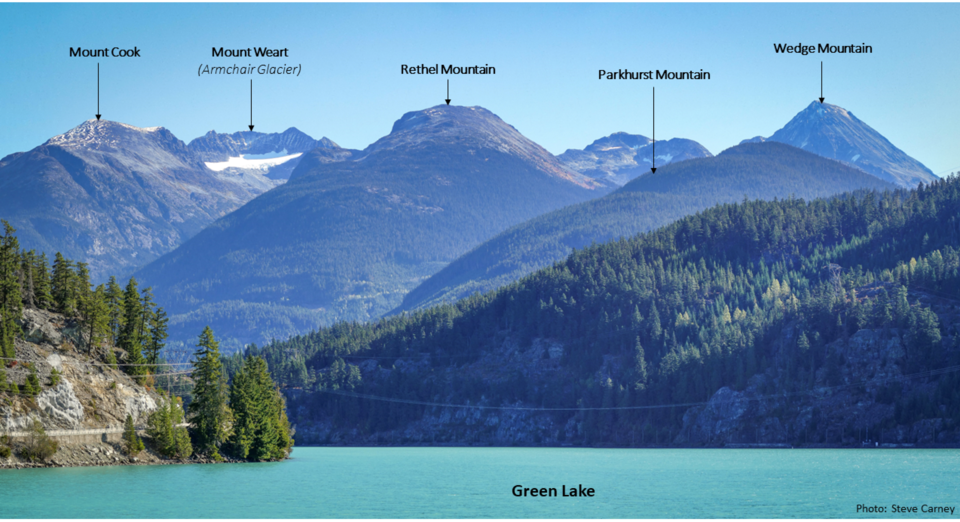

Around Whistler, only the highest peaks such as Wedge, Weart, Cook, Blackcomb and Whistler mountains protruded above the sheet, forming jagged islands of rock in a sea of ice. Glaciers followed ancient drainage patterns and eroded the valleys into distinctive, steep-sided, U-shaped troughs. When the ice finally retreated, some tributary valleys, such as Wedgemount Creek, were left “hanging” far above the valley bottom.

The high mountain peaks show clear signs of glaciation, such as the Armchair Glacier with its circular “cirque” basin, steep “arrêt” ridges and pointy “horns.”

The lower mountains such as Parkhurst were covered by ice and are smooth and rounded, worn down by the glaciers and covered with distinctive rock mounds called “roche moutonnée” (sheep backs). These erosional features have a smooth, polished upper surface and a steep drop-off at the front creating awesome natural ramps much loved by Whistler’s mountain bikers following the ancient pathways of Ice Age glaciers.

Adjacent to the lake there are some incredibly beautiful but fragile modern environments like the Fitzsimmons Creek Delta, formed where the Fitzsimmons Creek enters Green Lake. On entering the lake, the creek slows down abruptly and sediment carried by the water is deposited forming the delta. But not all sediment is deposited immediately—some tiny, silt-sized particles known as “rock-flour” remain suspended in the water for days or weeks. The light reflecting off this silty water is scattered at a frequency we see as green, hence the name “Green Lake.”

There are also some important wetland areas around Green Lake at the River of Golden Dreams and Wedge Park, near Whistler Secondary School, which are rich in flora and fauna. First Nations utilized these areas and had summer settlements here for thousands of years.

In 1916, the Alta Lake Mining Company began mining for iron here, amazingly producing 150 tonnes of iron per day at its peak, which it transported by railway to Squamish, then onward to Washington state. The metal originated from iron-rich minerals within the Coast Mountain igneous rocks, and was transported in groundwater and runoff into the lakeside bogs where it oxidized and was deposited as “bog iron.”

The pioneering miners are long gone, but not the bog iron—it’s highly likely this renewable resource has been replenished and is again lying on the bottom of the wetlands around Green Lake.

Naturespeak is prepared by the Whistler Naturalists. To learn more about Whistler’s natural world, go to whistlernaturalists.ca.