Mary Thor charged through the smoke down her treacherous driveway in the little Toyota. With one hand gripping the family dog and the fire literally exploding trees behind her, she headed for the strip of washboard road cut into the side of the mountain that she hoped would eventually lead her to safety.

It was July 27, and evacuation notices had been issued for all of the country affected by the raging Casper Creek Wildfire that was threatening the entire area near Anderson Lake. It was a hair-raising 30-kilometre drive, and Mary was on her own. Her husband, Bernhard, had stayed behind to fight the blaze, and she wasn’t sure she would ever see him again.

In what was likely a very short discussion, Bernhard had made it clear he wasn’t about to give up a life’s work because of some forest fire. Besides, he had been preparing for this day for years, every season clearing ground cover and cutting firebreaks to mitigate a possible spread. In the end, it was that, along with a ready water supply and an indefatigable constitution, that made him think he might have a real chance of saving the land. When the fire finally approached the house, he was ready.

A work of art

Bernhard and Mary Thor have lived on the mountain for more than 50 years. Like myself, Bernhard staked property in the days when the province of B.C. saw fit to open up land to settlers. On that stake north of Whistler B.C., he built his home. But not just any home. A multi-faceted man of the arts, he used all of his skills as a sculptor, stone mason and painter to build a dwelling that was, itself, a piece of art. That, along with some incomparable bush skills, made him one of our few true modern day Renaissance men—a fact only outshadowed by a remarkable early life.

His upbringing reads more like a piece of thriller fiction than a childhood. Born in East Germany, he escaped the political oppression of the Soviets by making a run for it through a no man’s land of minefields, razor wire, electrified fences and booby traps—all overseen by guard towers and machine gun nests. The whole thing took some serious intestinal fortitude, and it’s a miracle he is alive to tell the tale. What he didn’t know was that one day he would need every bit of that snot and vinegar to face the raging wildfire that would threaten his house and land.

Fire and fury

This summer was the worst on record for forest fires, both in B.C. and around the world, and the area north of Pemberton didn’t escape their fury. The final cost in human suffering and loss of property has yet to be determined. The projections, however, are staggering.

This kind of frequency is unprecedented. Between 1984 and 2015, the number of forest fires in the west doubled, and the last several years have seen some of the worst results of that increase. My partner Lynn and I narrowly missed one of the most dramatic fires in B.C. history when we chose not to stay at the Lytton Motel on the night of June 29, 2021, deciding instead to push on to Vancouver. The following day, as we now know, a raging wildfire burned the town to the ground. It was the sheer luck of the draw.

The firefighting community has struggled to keep pace with this new reality, throwing everything they have at the problem, from equipped, trained and air-supported fire crews, to modern technology ranging from satellite imagery and infrared scanning to fire modelling. But they need help from the public. The people on the land can do a great deal to protect their own and their neighbours’ property by taking a few simple steps, and Bernhard Thor might be a living example of how that’s done.

A mythical struggle

It was late in July when the fire soared up the steep ridge towards the property, turning what began as a simple sighting of smoke into a mythical struggle for survival. Bernhard didn’t waste time in responding. Alternately soaking land, buildings, and slashing bush, he fought off the flames with everything at his disposal.

Over the years, he had developed a complex sprinkler system to water the extensive acreage that hosted, amongst other things, a huge vegetable garden, a workshop and several sheds. He expanded this to allow the continual watering of the roof of the house. That, he hoped, along with several strategically placed fire breaks and a cleared forest floor, would be enough to save the property.

When it became clear he wasn’t going to abandon the land, the fire crews in the area took the opportunity to make it a base for operations. But not before the police were called in to try and persuade him to evacuate.

When they arrived, they asked him what he was still doing there.

The reply was pure Bernhard.

“I don’t like to run away from trouble,” he said. “I prefer to run towards it.”

There were some raised eyebrows from the fire crew, along with a little poking at the ground and staring into the distance as they slowly digested who they were dealing with. Then all of a sudden, one by one, they started to laugh. And that was that. They settled down at that big old kitchen table and put together a plan of action.

Firefighting is a complicated and dangerous business. Above all, though, it is extremely hard work. In the days that followed, those crews laboured to save the properties on the side of that mountain with a dedication that can only be described as Herculean. Meanwhile, Bernhard continued to cut, clear, and water day and night, taking only brief naps when he could no longer stand up.

In the end, it all paid off, because when a worried Mary Thor returned after 10 days of living out of her car, she found her house still standing and her husband alive and well... more or less, anyway. Bernhard was worn right down to the nub. He was, however, according to Mary, “sporting a very large grin.”

That land now sits like an emerald on the face of the mountain—a tiny oasis that stands as a monument to the human spirit.

Words of wisdom

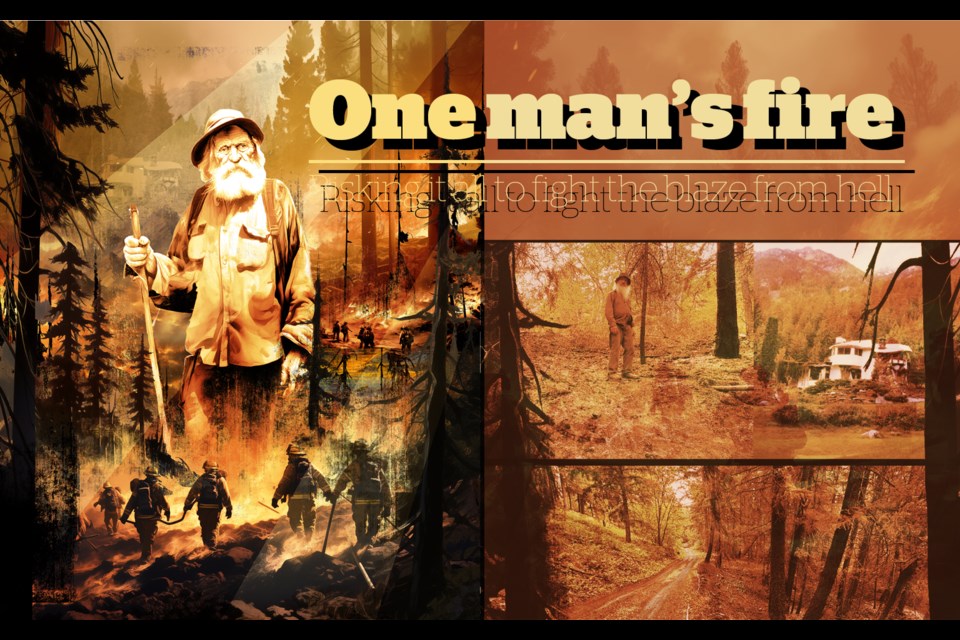

We visited Mary and Bernhard immediately after the fire. After talking our way through the road blocks, we wended our way up a damaged track towards the property. Even after disaster, this country remains spectacular, and the views from this wild and rugged road continue to take my breath away. The devastation we found, however, was chilling. In that peculiar way a forest fire burns, it had charred entire mountainsides while leaving certain areas untouched, so much of it dependent on the prevailing wind and weather.

Relief flooded over us when we saw that the house and land were still intact. Bernhard and Mary are our friends, and the thought of them losing a life’s work to fire had been haunting us for weeks. We had a fine old celebration that night. Lynn dragged out her accordion, I grabbed my guitar, Mary cooked a monster dinner and Bernhard went to raid the beer cooler. It was the best of all possible endings.

After his brush with death, Bernhard had some words of wisdom for to all those willing to listen.

“The best way to protect a community from forest fire is by removing the ground cover, cutting effective fire breaks and continually watering the land and buildings when property is threatened,” he said.

What he failed to mention was that it also takes an inordinate amount of courage to stand up to these natural disasters. When asked if he’d had any sort of “Plan B” in mind if things had gone south, he just shook his head and replied with, “Well, if push came to shove, I figured I’d just grab a cold beer, head out to the pond, cover myself with a wet horse blanket and wait.”

Yep. That’s pretty much the man in a nutshell.

Whether or not we are living through a world-wide paradigm shift where seasonal fires have be-come the norm is, at the moment, unclear, but 2024 promises destruction just as devastating as what we’ve seen this summer. How we choose to handle this ballooning threat may well determine our future on this rock. Firefighting skills and technology will no doubt improve, but a lot depends on how individuals and property owners handle themselves.

Let’s take Bernhard Thor’s advice to pay attention and prepare the land around us for what appears to be a very real threat to our well-being.

Paul Lucas is a musician, writer and composer who lives part of each year off the grid in his cabin south of Atlin B.C. His latest book, A Guitar Player On The Yukon Border, is available at local bookstores and amazon.com. He can be found at: paullucasmusic.com