The fine china failed to appear this year. Ditto the starched linen tablecloth and matching napkins. Neither of us got up early to stuff the bird and fill Smilin’ Dog Manor with the rich smell of roasting turkey. There was no cornucopia, no groaning board of traditional foods and fattening desserts at our house this year.

Despite that, it was not a virtual Thanksgiving this year. We enjoyed the relative freedom of our vaccinated status and celebrated both Thanksgiving and our imminent return back to Whistler at the home of good friends.

I’d offered to do the turkey, largely out of a desire to concoct my favourite cornbread, sausage, green chile, piñon nut dressing. But our hosts insisted on reserving that aromatic honour themselves. Just as well. After a recent roasting of chicken, I suspect the oven may need cleaning lest it burst into flames from whatever spattered all over and will happily wait until sometime next year to be cleaned away. The only scullery duty more odious than cleaning an oven is turning on a self-cleaning oven and imagining the entire kitchen go up in flames from the intense heat while I’m lying prostrate on the floor having choked myself into unconsciousness from the fumes.

Besides, relieved of the only culinary duty other than whipping up dessert—Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s molten chocolate cakes, an impossibly decadent dessert no one believes is so simple—I have time to reflect on some of the many things for which I give thanks.

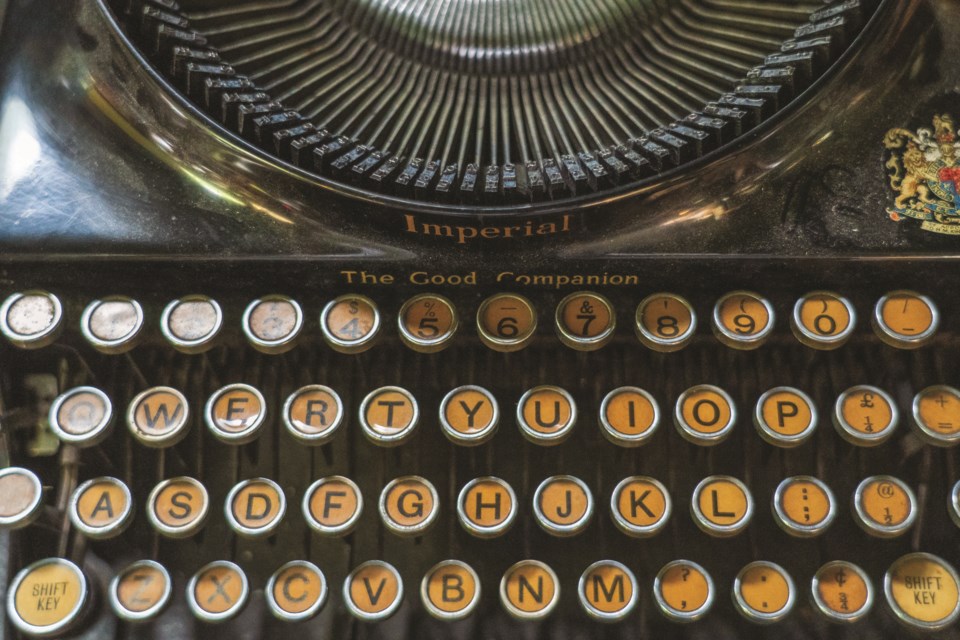

Typing, for example.

In Grade 10, I was short one elective and perplexed about what to take. I perused the list of Guy Electives, looking for something interesting. There was Auto Identification: 1957-1967, The Classic Decade. Strange Sports Statistics, offering the advantage of half a math credit since it was as close as some of us ever got to studying statistics. Small Appliance Dismantling, a dual elective coupled with the Theater Department’s classes in Puzzled Looks and Miming Innocence. Sadly, none of them really caught my interest.

I had it down to a choice between Creative Sibling Torture and Baseless Bragging when my mother said, “Why don’t you take typing?”

“Typing’s a girl’s class,” I replied. Remember, this was a time before Gender Enlightenment.

She gave me a look I didn’t see too often but translated roughly into, “How could I have gone through labour for you?” What she finally said was, “I thought you liked girls? Besides, you’ll never regret learning how to type.”

It had previously occurred to me before there was something to be said for being the only guy in a class full of young women whose passions may have been aroused in the previous class studying Romantic English Poetry or something of that ilk. But typing! I couldn’t imagine anything more geeky or more likely to invoke convulsive laughter amongst my friends.

But there I was, me and one other guy in a class of about 35 future secretaries. He looked the part, right down to a pocket protector protecting his polyester shirt from the matching Cross pen and pencil poking out. I, of course, looked cool if grossly out of place, an absurdly subjective opinion.

First class he sat next to me. Concerned I might catch Raging Geek from him and pissed off he’d wasted a seat that may have been occupied by my amour du jour, I told him if he ever sat next to me again, I’d break his thumb—the one you hit the space bar with. He said we fellows should stick together. I said we should divvy up the class and do our best to get a date. After a painful explanation of odds making, he finally understood.

My mother was not a visionary. She did not foresee personal computers or the future importance of knowing your way around a keyboard. If pressed, she may even admit to motives of self-interest. She knew who would end up typing my papers if I didn’t learn how. And she’d seen my handwriting.

On a very regular basis, like this morning, when I sit down in front of my taunting blank computer screen, I give thanks for her foresight.

I give thanks for Christmas, 1986, the year I first inflicted my family on the woman I’d eventually marry. She and my younger sister, while in the throes of advanced eggnog poisoning, conspired to pull a practical joke on me: They decided to take me skiing.

I had never been skiing. I thought riding chairs to the tops of mountains and sliding down on waxed boards was a pretty wussie way to earn your mountain. Anything short of hiking up and glissading down was both way too frou-frou and, for most of my life, way too expensive to merit serious consideration.

They arranged equipment and said they’d teach me, so I agreed to go. Well, actually they called me a coward, belittled my manhood and made those awful chicken clucking sounds when I told them they were out of their minds, so really, I didn’t have much choice.

Having climbed and hiked virtually every nook and cranny of Sandia Mountain—the eastern border of Albuquerque, New Mexico—I felt supremely comfortable taking up their challenge. It was my mountain. The craggy side, not the ski side. At least until I put skis on. At which point, it became the Twilight Zone, a place where the laws of gravity became threatening.

For the first half of the first run—of course they took me to the top of the mountain—I was convinced Go-Turn-Fall was the only possible way any human could ski. The fact they didn’t seem to execute the Fall part nearly as often or as well as I did changed nothing. I was also convinced it was a normal part of learning to ski to scream, “I’ll kill you if I ever catch you!” at people you love under normal circumstances and would never, ever think of as at all bitchy.

But somehow, by the time we reached the bottom of the mountain, I had developed a pattern of Go-Turn-Go-Turn-Fall and was so encouraged by this clear show of progress, I skied right onto the chairlift. My enthusiasm surprised both of them, the liftie and the person ahead of me about to sit on the lift who surprisingly ended up on my lap. But I was hooked.

The rest is personal history. I took an early pardon from a life sentence at a financial institution that shall remain nameless, sold my house, moved to Whistler and convinced Bob Barnett to let me tell you stories like this.

For which I am truly thankful... even if you’re not.