In Alta Lake's early days, there were no grocery stores or farmers' markets. Shipping fresh food up from Vancouver was expensive and unreliable, so Alta Lake residents procured as much food locally as possible.

Fresh vegetables were especially hard to import, so virtually everyone had a large garden. Today, fresh, local produce is treated like a delicacy; back then it was the norm. All summer long residents and visitors alike dined on greens mere yards from where they were plucked from the rich valley-bottom soil.

Needless to say, winter was a different story. To fend off culinary boredom (not to mention scurvy), locals spent much of the fall preparing produce to keep through the cold, deep winter.

Most year-round residents kept root cellars, something which our Pembertonian friends are familiar with. With no refrigerator, Parkhurst Mill housewife Eleanor Kitteringham depended on this vital household appliance to keep her family well fed: "There was a door cut in our floor in the kitchen, with a leather handle to lift and stairs going down under our house to put potatoes, carrots, cabbages, etc. in, as well as shelves for canned goods."

Demonstrating pioneer-era resourcefulness, Eleanor remarked how the root cellar "also made a great dark room to develop pictures in."

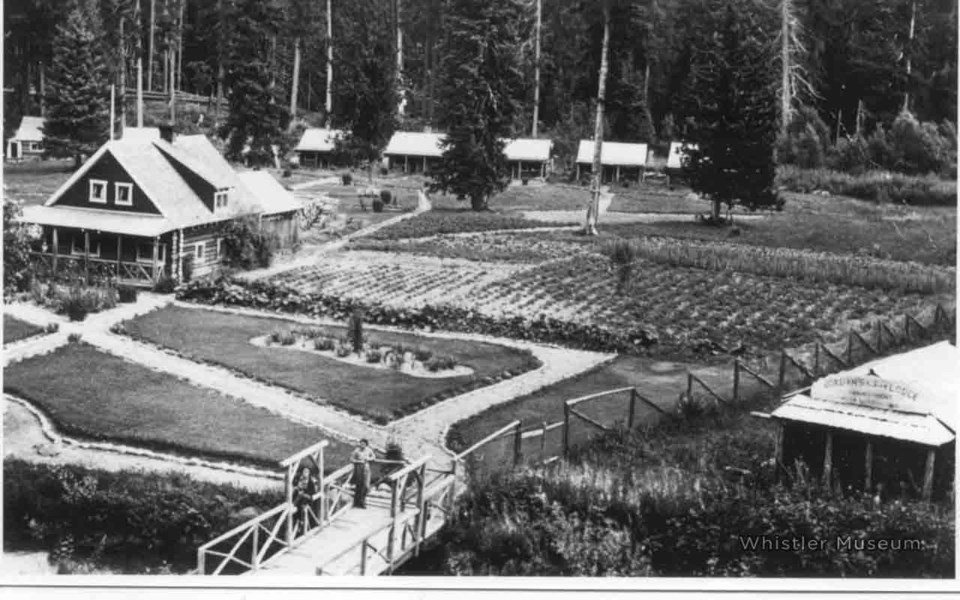

The alluvial fan between Nita and Alpha Lakes, near where Nita Lake Lodge is today, was one of the best growing sites. In the 1920s Harry Horstman had a small farm there, the produce from which he sold throughout the Alta Lake community. Russ Jordan bought most of this land from Horstman, building Jordan's Lodge (pictured above) in 1931. Jordan maintained a large, orderly garden to help provision his guests.

Much of the canned and pickled goods were produced locally, preserving excess produce drawn from backyard gardens. The museum has a recorded interview with Myrtle Philip, describing her preferred techniques for making jams and jellies (these were made primarily with boxes of Okanagan-grown fruit).

Myrtle made jams from wild, local berries, crabapples, peaches and much more. It turns out Myrtle thought most people used too much sugar, and that she preferred jellies to jams (jellies have the seeds and pulp strained out using cheesecloth). The most remarkable aspect of the interview is that Myrtle was making apricot jam while the interview was being recorded in 1982, at the ripe old age of 91! Today we take such things as fresh pineapples in February for granted. Back in the day, if you didn't work for it, you didn't get it.