The B.C. government routinely understates its budget forecast each year, typically resulting in annual surpluses that have become more pronounced in recent years, say economists.

And it is these surpluses, or less severe deficits, combined with billions of dollars of future “fiscal padding,” that indicate the province can afford to make major new public investments to address crises in housing, climate change, health care, child care and toxic drugs, argues economist Alex Hemingway for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives-B.C. in a white paper published Nov. 2.

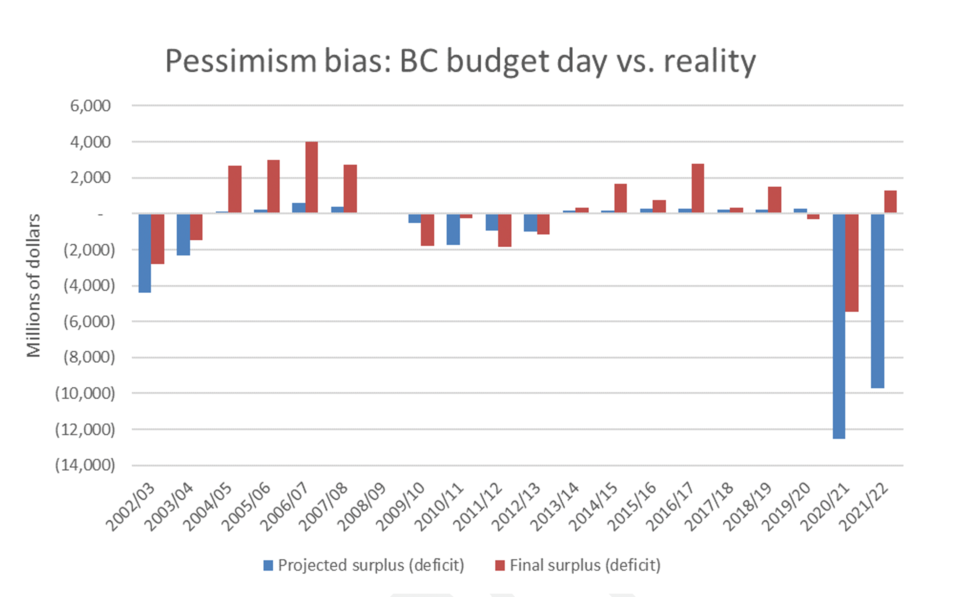

Hemingway says the B.C. Ministry of Finance has a “pessimism bias” that is leading to systemic curtailment of public spending on social improvements. Over the past 20 years the annual provincial budget forecast has closed with higher-than-expected net revenue in all but three years, Hemingway shows.

“There seems to be a political imperative to end up with a surplus at the end of the year or end up with some sort of pleasant surprise. And so, we have a budget process that lacks transparency in a way, so if we're trying to have a democratic debate at budget time about how to allocate our resources …we need to be given a clearer and more realistic picture of what the budget situation is,” said Hemingway.

The pandemic resulted in the largest sways in budget forecasts and outcomes. Last year the provincial government originally projected a $10-billion deficit, but by year-end it had turned into a $1.3-billion surplus, Hemingway noted.

And over the next three budgeted years the government has factored in $20.2 billion of “fiscal padding” comprising of general contingencies, forecast allowances and future priorities. In 2017, the government allocated just $750 million in unknown expenses.

H emingway acknowledges there appear to be more uncertainties in recent years, such as with the pandemic, climate change and unstable global economic conditions. However, the next three budgets are "extreme,” he says, and the government should be more accepting of annual fluctuations between surpluses and deficits, “rather than biasing things in one direction just so we avoid a headline of a deficit.”

emingway acknowledges there appear to be more uncertainties in recent years, such as with the pandemic, climate change and unstable global economic conditions. However, the next three budgets are "extreme,” he says, and the government should be more accepting of annual fluctuations between surpluses and deficits, “rather than biasing things in one direction just so we avoid a headline of a deficit.”

End-of-year surpluses are designed under law to lower government debt, notes Hemingway, and to correspond with these frequent surpluses, B.C.'s operating spending has declined as a share of GDP, from 21.5 per cent in 1999-2000 to a projected 19.4 per cent in 2022-2023 and 18.6 per cent by 2024-2025.

Hemingway says all of this is to suggest the provincial government has the means to invest more money to tackle various crises, which falls in line with the centre’s overall position that government can play a larger role in doing so.

“I think that's not an uncommon perspective. But I think a lot of folks would say, ‘Is that realistic? Do we have the economic capacity to do that?’” said Hemingway, to which he replies, yes.

Hemingway says if the government spent at levels in the year 2000, measured by percentage of GDP, it would have about $10 billion more to spend this year.

And so, the roughly $7 billion of annual unallocated contingencies over the next three years should actually be allocated to address housing, climate change mitigation and the drug poisoning crisis, argues Hemingway.

“From the outside, to me, it looks like a sort of a political manoeuvre to under-promise and over-deliver when it comes to the budget-balance situation,” he said.

Hemingway and the centre say the BC NDP has unnecessarily taken fiscal conservative positions, such as choosing five mandatory sick days over the10 the public majority wanted. Nor has it taxed the ultra wealthy more, which has broad non-partisan support and is feasible according to credit rating agency Moody’s, Hemingway notes.

And, many of his proposed investments can pay for themselves over time, says Hemingway, such as with non-market housing.

Hemingway argues senior governments need to build rental homes and co-ops as they did in the 1970s and 1980s. The government can buy land, construct the housing and have the loans paid back with working class wages paying the rent over the mortgage period; this strips away the roughly 15 per cent private sector developer profit.

“We want to address these issues and not be stuck in a sort of mindset of scarcity that actually doesn't exist in what is ultimately an extremely wealthy province,” said Hemingway.

In a statement to Glacier Media, Minister of Finance Selina Robinson acknowledged how all Canadian provinces have experienced surpluses during the pandemic years.

"When we recognized we had a forecasted surplus earlier this year, we provided an additional $1 billion in funding for affordability measures for people in B.C., like boosting the BC Family Benefit, the Climate Action Tax Credit and supporting families in need with back to school expenses.

“We still face global economic uncertainty and new challenges — but we know we’re in a strong position to continue investing in the things people need to reduce costs, strengthen services and build a stronger B.C. for everyone," stated Robinson.