In this excerpt from Heard Amid the Guns: True Stories from the Western Front, 1914-1918 (Heritage House, 2020), a profile of the author’s grandfather Charles Chapman, who settled in Port Alberni after being wounded in the Great War, Jacqueline Larson Carmichael sets the tone for this collection of personal stories that capture the stark realities of war and its lasting effects from generation to generation.

In 2016, a hundred years after the Battle of the Somme, a clerk at the Enterprise Rent-A-Car counter in Amsterdam smiled broadly at me. “You rescued us — twice!” she said. She had just learned that I was Canadian.

“You’re welcome,” I said, smiling in return.

On a research trip to Belgium and France, I was about to experience the powerful effect the former Western Front in Flanders, Belgium, and France had on my ancestors. The two major arenas of the First World War were within an hour’s drive of each other. I was startled by the close proximity of the places my grandfathers fought, where waves of hundreds of thousands of soldiers poured over the gently rolling landscape.

That land is still, in many cases, pitted with craters and trenches. Each year, bomb disposal units find thousands of kilograms of unexploded ammunition on the former Western Front. So, when a sign says DO NOT WALK ON THE GRASS, I don’t walk on the grass.

Things I had long been told about my grandfather, Oklahoma-born George “Black Jack” Vowel, led me to even more questions. I knew that he died in his early 60s when his tractor overturned on him in the Peace River Valley. I knew the wartime words penned in letters to Louisa “Bebe” Watson Small Peat lived on: CBC Radio based a radio program on them in 1992, and then Peat’s daughter gave them to my aunt, Peggy Aston, who passed them along to me.

I had transcribed them for a number of articles in the Edmonton Sun, Alberta Views, and other publications, eventually giving George “Black Jack” Vowel a social media persona and tweeting his words as if I were him, in an effort to tell a new generation about his life in the trenches of the First World War. But being in the trenches where he and my maternal grandfather both fought — that was a different experience altogether.

I had transcribed them for a number of articles in the Edmonton Sun, Alberta Views, and other publications, eventually giving George “Black Jack” Vowel a social media persona and tweeting his words as if I were him, in an effort to tell a new generation about his life in the trenches of the First World War. But being in the trenches where he and my maternal grandfather both fought — that was a different experience altogether.

I am the second-generation product of two soldiers of the First World War. Both grandfathers, prairie ranchers, were in the war for the four-plus years that Canada fought — like so many others. They survived, but they never talked about it. Despite the surface similarities of their backgrounds, the war impacted them in very different ways — ways that would be handed down (for better or worse), like psychological heirlooms, to their children and their children’s children.

Somewhere in the trenches of Flanders, on the rolling hills of the Vimy countryside, I hoped to find answers to the questions that had been sparked within me.

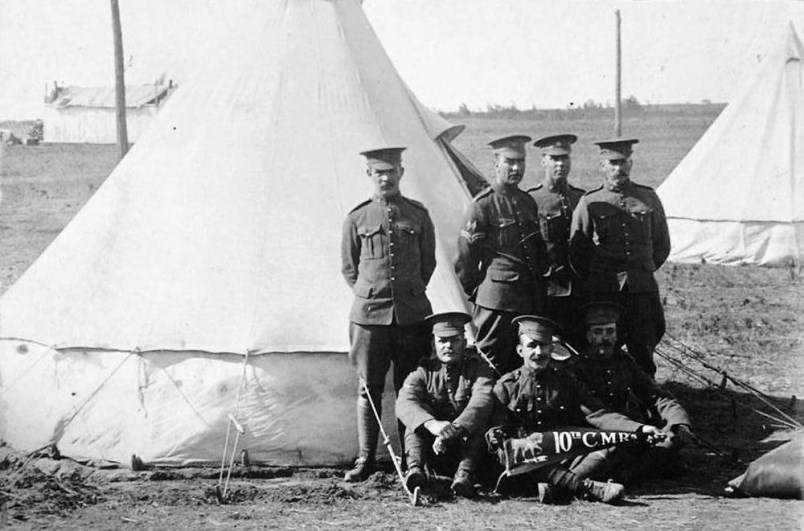

My maternal grandfather, Charles Wellington Camden Chapman, was a young Saskatchewan rancher at the outset of the Great War, and a volunteer who signed up in November 1914.

The cowboy son of an Anglican minister and adventurer, raised partly in the far north of Churchill, Man., Charlie was an artillery man, operating a gun that lobbed eighteen-pound shells at “Fritz,” as the German Imperial Army was dubbed. He was wounded in the leg on Oct. 13, 1915, and shrapnel from the shell was embedded in his back. He was in hospital for sixty-nine days.

After occupying Germany, Chapman came home whole, as far as you could tell, despite his obvious wound. He had a slight limp in his walk and was a bit hard of hearing. Every so often he’d go to the veterans’ hospital, and they’d take another piece of shrapnel out.

He had kind blue eyes that crinkled at the corners and a hearty laugh that rattled in a chest damaged by mustard gas. He married a lovely Canadian girl named Ruth Showalter, who was of French and German stock.

Photos with their six kids show a happy family. But Maidstone, Saskatchewan, was a Dust Bowl bust, so they sold the farm for the price of a rickety Ford Model A, into which they loaded up the clan, with suitcases tied to the running boards and mattresses strapped on top, like Joads from John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath.

They went to Ladysmith, Nanaimo, and ultimately Port Alberni, where Grandpa Charlie used a particular trick for getting a job: If you’re standing in a job line with hundreds of other men, and if they ask you if you have experience doing X, say “Yes!” even if you don’t; figure out how to do X later.

Eventually, he finished his career as a foreman at Bloedel, Stewart and Welch’s chipper plant. He was a good Royal Canadian Legion man, but he never talked about the war. In fact, he tried to forget about the war. When Charlie Chapman’s kids asked him if he killed any Germans in the war, he grinned and said he only practised on bully beef tins.

He was either a loyal hero or a glutton for punishment: Even after four long years in the First World War, he wanted to volunteer for the Second World War. Told he was too old to enlist, he served in the home militia. He didn’t have a perfect life, but he was a genuinely nice guy — cheerful, kind, nurturing, beloved by his children and grandchildren.

Charlie Chapman outlived three wives, but not his sense of humour. He bore his decline gracefully and played a mean harmonica with dignity in the kitchen band at the seniors’ home in Parksville. He numbered among his friends Tommy Douglas, founder of the NDP and Canada’s socialized medicine.

And upon his death, he was laid to a hero’s rest with his fellow veterans in Port Alberni’s Field of Honour — not far from the resting place of his brother-in-law, First World War veteran Guy Showalter — under the shadow of a tree grown from an acorn that came from Vimy Ridge.

Visit heritagehouse.ca.