The B.C. government is offering the first look at parts of a $460-million plan to plug a growing labour gap as employers struggle to fill jobs.

The province has budgeted $126 million in the next year for skills training, helping immigrants to have their credentials recognized and helping businesses hire staff.

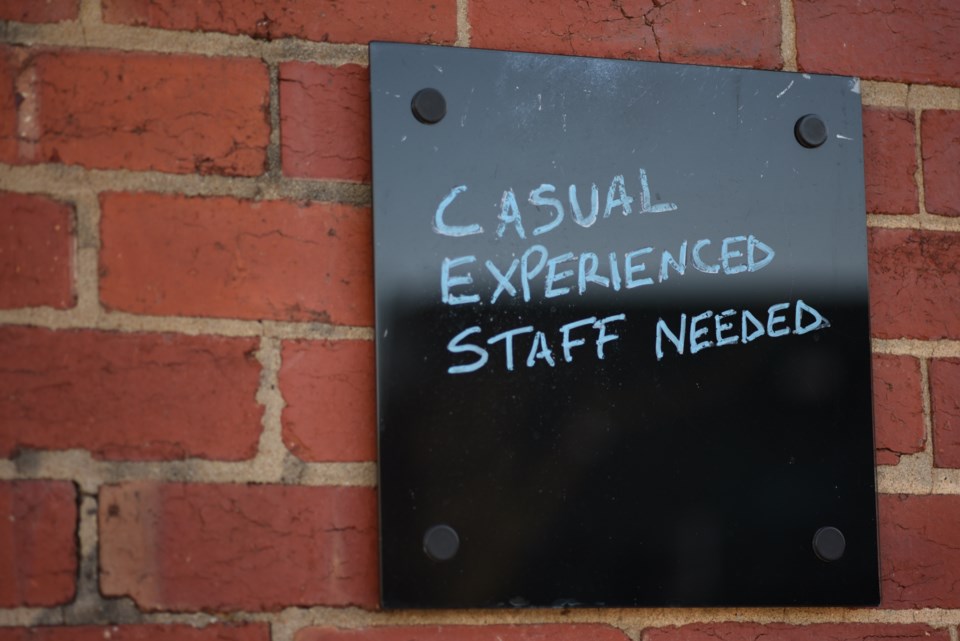

Finance Minister Katrine Conroy said lack of staff is the number one issue for small businesses in the province.

“We need to get more people into the province. We need to get more people trained. We need to get more people trained in the industries that need more people,” Conroy said when the budget was released last week.

B.C.’s latest labour market forecast estimates the province will add roughly 400,000 new jobs by 2032. It created 96,000 net full-time positions in 2022, the province says, leading to an unemployment rate of just 4.4 per cent in January.

The flipside of that good news story is a complicated economic conundrum. Businesses in sectors like food services and construction say they simply can’t find staff. And workers’ wages aren’t keeping up with inflation, even though their labour is in high demand.

That’s heightened demand on government to find solutions, either by expanding training for sectors like the skilled trades or helping businesses hire workers who are underrepresented in the current job market.

“We cannot manufacture people,” BC Chamber of Commerce president Fiona Famulak said. “We cannot create people, so we have to face the reality that there are not enough people to fill the job opportunities now or in the future.”

B.C.’s answer to the problem is the Future Ready Plan, a $460-million strategy the government plans to roll out over the next three years.

The budget is scant on details of how the money will be allocated, but the plan is expected to include $39 million for short-term skills training, $58 million to help newcomers and immigrants certify credentials in Canada and an undisclosed sum “to assist small and medium-sized business in finding and implementing practical solutions to current labour market challenges.”

The budget also hints the plan will “maximize workforce participation” by spending cash on training early childhood educators, health-care staff and workers in the tech industry.

The Finance Ministry would not offer further details on how that money would work or how the cash would be allocated. The full plan is expected to be released in the coming months.

Already, the low unemployment rate has many businesses in the province scrambling for staff. Some industries like construction and food services are increasingly relying on the federal government’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program to fill positions. And the government expects that trend to continue as a rising number of workers retire.

The province forecasts the labour participation rate – the number of eligible people who are employed — will tumble from 65.1 per cent last year to 62.2 per cent by 2027 as workers leave their job.

But some argue that those figures are overly pessimistic, and that framing the problem as a “labour shortage” is a mistake.

“I hate that term. I just hate it. I cringe when I hear it,” said Jim Stanford, a labour economist and director of the Centre for Future Work.

Stanford argues the unemployment rate masks the fact that many workers are “under-employed” and would take better jobs with longer hours if they were available.

He also says many demographics — including women, Indigenous people and people with disabilities — are underrepresented in the labour force and could fill more jobs if they were offered the training and support to do so. “You’ve got potentially pools of labour supplies that haven’t been captured at all,” Stanford said.

Conroy noted that 75 per cent of the gains to B.C.’s labour force last year were for women, something she attributed to new federal and provincial spending on child care.

Stanford’s frustration with the “labour shortage” is that it frames the economy’s problems as the fault of workers instead of putting the onus on employers to attract workers by offering better wages, hours and other working conditions.

“A labour shortage is a very biased term, and it also, I think, misrepresents exactly how much slack there still is in the labour market in Canada,” Stanford said. “There’s a lot of slack.”

Sussanne Skidmore, the president of the BC Federation of Labour, says she wants more details on how B.C. plans to train the workforce of the future. She says she’s particularly hoping for investments in training for key skills and careers that will support well-paying jobs.

“We’re hearing this piece around worker shortages, but we know that in a lot of sectors we’re hearing about issues. It’s not just about wages but also treatment of workers,” Skidmore said.

What Skidmore doesn’t want to see, she said, is a reliance on temporary foreign workers to fill labour gaps. That federal program allows businesses to hire foreign workers on short-term contracts when they can’t find someone domestically.

B.C. businesses applied for a record number of workers last year, and the province’s Employment Standards Branch received more than 12,000 applications from interested employers last year alone, particularly in sectors like construction, agriculture and food services.

Critics say workers in that program are underpaid and vulnerable to exploitation. Skidmore and the federation have argued workers who come to Canada should gain permanent resident status so they can move jobs and negotiate better salaries.

“We have a really strong opinion in the labour movement that if folks are good enough to come here and work here in our country, they are good enough to be treated the same way,” Skidmore said.