The cheapest way to exit the Whistler bubble is through a book. The bonus is that from the comfort of our over-priced, under-insured homes, we not only escape to myriad elsewheres, but also return better informed about the glossed-over realities and greater machinations of the world. In that vein, I want to share a few worthy science-related non-fiction titles:

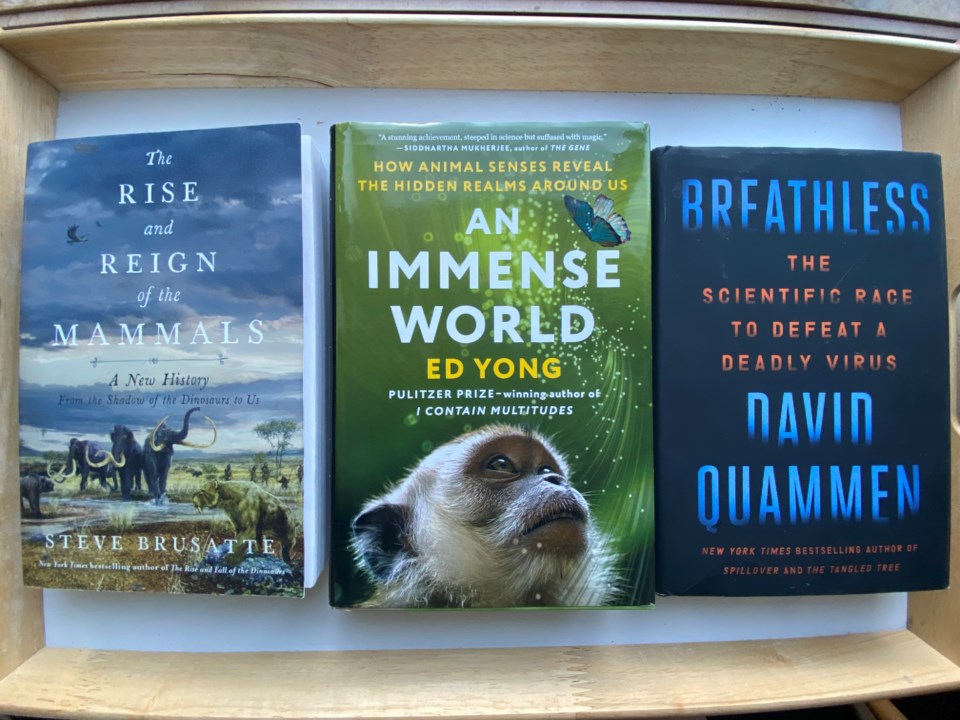

The Rise and Reign of the Mammals: A New History from the Shadow of the Dinosaurs to Us

Paleontologist Steve Brusatte made a name with 2018’s Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs, a New York Times bestseller that covered the latest science on everyone’s favourite monsters under the bed. But while people might know something about dinosaurs, they know less of their 165-million-year reign and what was happening simultaneously, evolutionarily speaking, literally at the feet of these beasts.

Brusatte picks up this thread with the tiny mammals who shared the planet with dinos, from the initial split into us (mammals) and them (dinos, birds and crocodiles), to the end-Cretaceous extinction and whispers of a mammal takeover built on new, complex dentition, hair, warm-bloodedness and the division of proto-mammals into monotremes (egg-layers like the platypus), marsupials (that carry developing offspring in external pouches), and placentals (whose babies develop internally). His treatment of the latter is most relevant as we seem to know precious little about our own family tree—or how, in the end, we came full circle to metaphorically act as a living meteorite contributing to the mass extinction of mammalian megafauna (mammoths, sabre-tooth cats, etc.) at the end of the last Ice Age.

An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us

Pulitzer Prize-winning science writer Ed Yong hit a home run with his breezy take on global microbiome research, I Contain Multitudes. This recent tour-de-force about the various senses animals employ and of which we (but not a central casting’s worth of dedicated researchers) are largely, blithely unaware, is also heading over the fence.

In the way you could never have imagined Yong’s previous revelations on how bacteria control the world, his unearthing of the many mindboggling ways in which animals perceive and engage with the world often leaves you in shock. In light, humorous style, Yong delivers another awe-inspiring read that places nature on the exalted pedestal from which we should always behold it.

Pro tip: skip the distracting footnotes while reading and return to them later.

The Devil’s Element: Phosphorus and a World Out of Balance

Phosphorus means “bringer of light,” a name earned in the 1600s when a German alchemist extracted from urine a strange, glowing substance that could spontaneously burst into flame. In other chemical configurations, it was soon learned, phosphorus was not only less dangerous, but crucial to life.

One of three key elements needed for plant growth (the others, as gardeners well know, being potassium and nitrogen), it’s also the backbone of DNA and critical to the structure and function of cells, bones and teeth. Thus, humans—and just about everything else—require it for life, and must obtain it through food. Egan takes us on a tour of the element’s heavy molecular mojo, its geologic cycle, use in nature, and co-option by humans for everything from fertilizer to fire bombs, showing how its value, abuse and a looming shortage of not-so-widely distributed phosphorous deposits could bring world agriculture to a standstill. Food for thought, so to speak.

The Feather Thief: Beauty, Obsession, and the Natural History Heist of the Century

I’m going back a few years here, but this 2018 standout is worth it. To begin, no true crime is more interesting than nature crime—yet another measure of our ignorance of a world that supports our own existence. As such, this book that could have been about nothing more than a misguided person compelled to steal valuable feathers for the criminal fly-tying underworld, but it goes far beyond by educating, entertaining and enlightening us in a way that might just put a dent in future similar crimes.

Riveting, engrossing and expertly told, The Feather Thief reminds us how obsession with any aspect of nature and an “unrelenting desire to lay claim to its beauty, whatever the cost”—whether feathers, ivory, fossils or exotic pets—can wreak havoc on our scientific heritage.

(For more on the unique world of feathers and fly-tying, check out Whistler poet Mary MacDonald’s recent Pique cover feature, “Hope is the thing with feathers,” March 17.)

Breathless: The Scientific Race to Defeat a Deadly Virus

If you read just one book about the COVID-19 pandemic with a mind to truly understanding it both in scientific terms and the human endeavours aimed at these, then science-writer emeritus David Quammen’s Breathless is my pick (I’ve read them all).

Unlike his other books—i.e., Spillover, the 2012 volume on zoonotic diseases that actually predicted the 2014 Ebola epidemic and even the emergence of SARS CoV-2—this one doesn’t find Quammen on the ground chasing down truths with researchers in the far-flung corners of the natural world. Instead it finds him doing so in far-flung laboratories via Zoom with almost 100 scientists and digging through the debris of the medical-literature explosion that paralleled the pandemic’s early days.

Eschewing the dullard world of politics, policy decisions and Facebook misinformation in favour of a science-only approach, Quammen’s tour through coronaviruses, virology, epidemiology, disease-origin scenarios and vaccination science make for, well… a breathless page-turner.