Journalists are expected to write the news and not be affected by the story. But that imperative became impossible for me two weeks ago, when I learned a friend had died while highlining.

Aside from trying to process the sudden loss of a valued community member and friend, I was also grieving someone close to me for the first time in my adult life. Perhaps I’m lucky to have made it this far without that kind of pain—but in this context, I can’t see myself as lucky at all.

Death is never easy. An unexpected loss flips your world upside down. We reject the premise that someone we held dear can no longer be held at all. What made it worse, though, was reading the poorly worded and sometimes sensationalized news coverage of the incident.

I felt hurt in two ways: as someone directly impacted by the story, and as a journalist who expects her colleagues to show due diligence in reporting the facts.

To be fair to reporters, highlining is a niche sport. Some people know about slacklining; fewer are familiar with highlining. The terminology is unfamiliar to many, so when the RCMP referenced a "slackline death" in their press release, many outlets ran with that phrasing—despite the fact the accident occurred while highlining.

One outlet, which I won’t name, took it a step further and made leaps based on what I can only presume came from unverified social media posts. The resulting article contained inaccurate assumptions that misled readers and damaged my community’s trust in the media’s ability to do their job with compassion and accuracy.

As I processed my own grief, filled in for our editor, wrote my own stories, and tried to support friends in any way I could, I found myself reaching out to various outlets to correct their reporting. I did so voluntarily, because I have the skills and media literacy many others in similar situations may not.

But these corrections shouldn’t have been necessary. I now have immense sympathy for those who’ve had to navigate this kind of media attention without knowing how.

When a tragedy occurs, journalists are tasked with explaining how and why it happened. Part of that job involves reaching out to those affected. It’s one of the hardest parts of what we do—and it should never be done without tact, respect and a deep awareness of the emotional toll involved.

We are often asking people in the midst of grief to go on the record about their trauma, before they’ve even had time to comprehend what’s happened. It’s an essential part of public information, but until this experience, I hadn’t truly understood what it felt like from the other side.

It was awful. It forced me to question how—and why—we report on death.

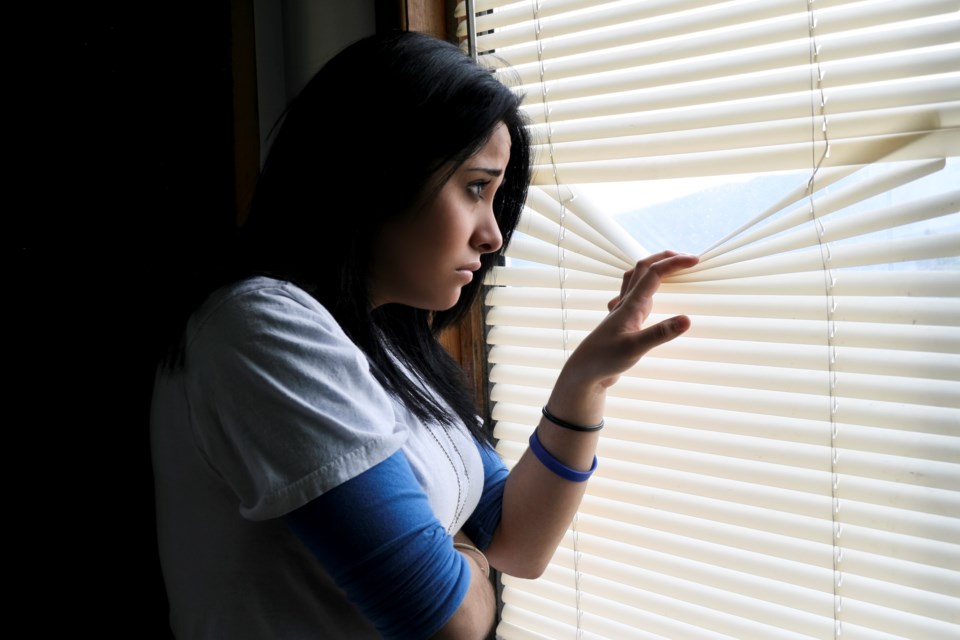

Some people are private and want to remain so. Others are retraumatized when a news story pops into their inbox. And the comment sections? They’re often filled with speculation and judgement, rubbing salt into wounds that may take years to heal.

In a time when public trust in news is already low—sometimes for good reason—this was the most difficult professional moment of my life. How could I defend my profession when some of what I saw barely resembled journalism?

All I can do is carry this experience with me. I will continue to report the facts. I will take care with how I approach those affected. I will rely on official sources when people at the centre of a story can’t or won’t speak. But most of all, I will extend compassion to the people behind the names in my stories.

Because while the media may move on, the people impacted never will. For them, this moment becomes part of their life story—and they deserve to be treated with care.