You hear a lot these days about habitat destruction, the loss of forests, shorelines, and wetlands, and the long-term costs of these to everything from the ecosystem services we humans rely on, to the planetary carbon cycle that threads everything together.

And while the pace of degradation shows no signs of slowing, there is at least one thing that's speeding up to meet the challenge: eco-restoration.

Ecological restoration is a robust discipline, evolving and gaining prominence (and not a moment too soon) within academia, industry, and government. It involves a wide range of professionals in the areas of biology, chemistry, agronomy, forestry, engineering and a range of crossover disciplines, making it a somewhat more technical milieu than, say, China's recent mobilization of 60,000 soldiers to plant trees. But how does this all come together when the subjects it traverses are as diverse as: mine reclamation; reestablishment of forest, salt marshes, and freshwater wetlands; fire ravaged landscapes; incorporation of traditional knowledge; and the debate over novel vs. natural ecosystems?

This was what I'd hoped to find out at "Restoration for Resilience," a conference staged by the Western Canadian chapter of the Society of Ecological Restoration at Simon Fraser University. Here, folks from around North America gathered to compare notes on what was working — and what wasn't — in propping up the earth's toppling ecological house of cards. "Resilience," was an apt word for the title given its relevance in global discussions around climate change, community, and biodiversity; building in resilience was proving de rigueur to ensuring that expensive and time-consuming ecosystem restorations aren't in vain.

There were talks on restoring habitat for butterflies, caribou and Garry Oak, on the effects of dam removal and salt, and on rebuilding urban ecosystems to maximize stored carbon and water filtration. In the session "Rising Tides in Marine and Estuary Restoration" I sat through illuminating presentations on the mechanics and results of restoration of an old log-sort site in the Squamish River estuary. The closing plenary address by Karsten Heuer — author, adventurer, former park warden and Yellowstone to Yukon Director — was downright inspiring. Now manager of Banff National Park's five-year pilot Bison Reintroduction Project, he is at the forefront of one of the continent's highest-profile eco-restoration efforts.

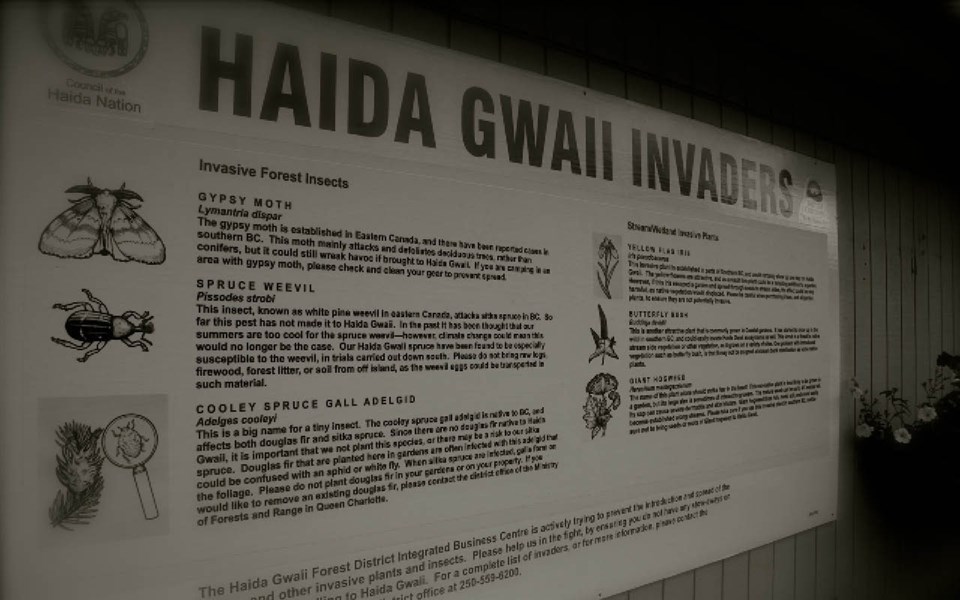

Unsurprisingly, some of the most ambitious and technically challenging eco-restoration projects in this country were also being undertaken by Parks Canada on a handful of islands in Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, National Marine Conservation Area Reserve, and Haida Heritage Site. Here, a program launched in 2009 under the pan-Canadian National Parks banner "Action on the Ground" saw Parks and the Haida Nation partner to restore salmon-spawning streams on heavily logged Lyell Island, and undertake rat-eradication on small islands that were formally important breeding colonies for endangered Cassin's Auklet and Ancient Murrelet — whose population here represents 50 per cent of the species' global total. The latter kicked off in 2011 with pilot efforts in Juan Perez Sound on Arichika Island and a small archipelago known as the Bishofs, being expanded in 2014 to the larger nearby islands of Ramsey, Faraday and Murchison. Clearing rats will allow for eventual return of the burrow-nesting seabirds, but already shrews and other small mammals previously depressed by the presence of rats have rebounded. Last year, Parks also began a program of removing invasive deer from Ramsay, Faraday and Murchison, in hope of restoring forest understory removed by over-browsing. The deer have altered soil and energy flows, turning once-diverse forests into eerie moss deserts with few plants, invertebrates or native songbirds. In a final effort, Parks will this year turn to the Gwaii Haanas ocean environment, attempting to restore kelp forests along part of Ramsay Island's shoreline that were transformed into barrens by hyper-abundant sea urchins; this will improve habitat for northern abalone and other kelp-forest species like rockfish that are ecologically, culturally and economically important. Collectively, these ecological shortfalls that the public would not be aware of are instructive of how even seemingly wild places can require considerable eco-restoration work to restore functionality.

Eco-restoration is an important frontier in conservation thinking. Not to put too fine a point on it, but as noted by Ingrid Stefanovic, Dean at SFU's Faculty of Environment, "...our sheer existence imparts a significant footprint upon the planet, degrading the environment from which we draw our sustenance. How we seek to restore the well-being and good health of those ecosystems... is a true measure of our humanity and our moral integrity."