I have a love-hate relationship with the fitness app Strava. On one hand, it works as a digital logbook of exercise and recreation routines, benchmarking big rides and letting me see what my friends and peers are up to on their bikes or running shoes. On the other, it can register inaccurate GPS tracks, skew data with horrible interpolation and worst of all, keeps poking me to sign up for the premium version.

The last time I wrote about Strava was in the previous incarnation of “The Outsider” in the now-shuttered Whistler Question in 2014. At that point, Strava had existed in the app marketplace for five years and was already well established in the cycling and running communities. I saw Strava as defilement of the social ride. One example in particular was a friend of mine taking off down a trail and leaving our group of friends for the next 20 minutes in order to attempt a leaderboard-topping Queen of the Mountain (QOM) time.

In 2014, Strava had no place in my mountain biking recreation, but like a lot of technology, it eventually seeped in via a combination of curiosity and peer pressure. I use it regularly now, though mostly to benchmark trails and rides against myself, not others on the leaderboard (trying to beat the likes of Jesse Melamed on the Westside will only result in a painful injury).

Strava’s success as a fitness app is pretty much attributed to its leaderboards. Uber-competitive users will get push notifications to their phone when they lose their QOM or King of the Mountain (KOM) status on a particular trail or segment. Training ensues in order to regain it and the addictive cycle continues. Love it or loathe it, Strava’s design is an elegant gamification of exercise and with a user base of more than 55 million people, it can probably take some credit for boosting daily exercise in our lifestyles.

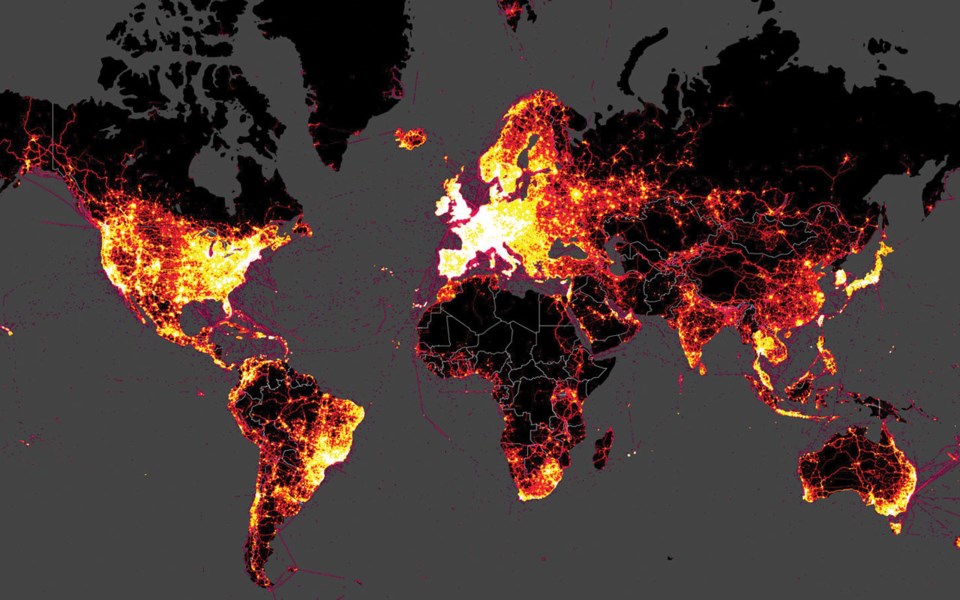

There’s always the sticky subject of privacy with an app that tracks your position and its susceptibility to being harvested by Big Data. Strava’s biggest controversy came after it published a “Global Heatmap,” a graphic representation of two years of trailing data from its global network of athletes. An Australian university student studying international security discovered that the heatmap had mapped military bases, including known U.S. bases in Syria and Afghanistan, and a U.K. naval base that contains the country’s nuclear arsenal. Safe to say that privacy controls were simplified after that and any user could opt out of the Global Heatmap.

But there are good things going on with the data of 55 million Strava users, too, albeit for profit. Strava Metro is an offshoot of the company that leverages aggregated and deidentified user data for the purpose of urban and city planning of cycling and pedestrian infrastructure. Not only is Strava used by people jogging around the block or hitting mountain bike trails, a lot of people use it on their daily commutes to work in urban areas.

The best thing about fitness apps is their statistics, something you had to go to the gym for before GPS location could be measured in your pocket or on your wrist. Every year, Strava compiles summaries not only of activities carried out by its individual members, but for the global community. Here are some highlights from 2019:

• For every one minute an athlete spends scrolling the Strava app they spend 50 minutes working out, on average.

• 3 hours, 58 minutes and 25 seconds is the average finishing time for a marathoner on Strava; 5.2 per cent of Strava athletes finished a marathon in 2019 and two per cent of runners endured an ultramarathon.

• Grouped rides cover twice the distance of solo rides on average. And they ride six per cent faster, too.

• Nine athletes climbed Mount Everest, but 3,059 athletes climbed the elevation of Mount Everest in one activity.

• Spanish athlete Kilian Jornet Burgada set the unofficial record for ski vertical in a day, climbing and descending 23,112 metres in 24 hours at Tusten Ski Resort in Norway. He was quoted as saying “I don’t know why I’m doing it.”

If any other smartphone app can boast these sorts of inspirational activities and habits, sign me up.

Vince Shuley took a few years to come around to Strava, but is glad he did. For questions, comments or suggestions for The Outsider, email [email protected] or Instagram @whis_vince.