SPRINGFIELD, Ill. (AP) — Illinois law now requires that prospective police officers approve the release of personal background records in response to last summer's shooting of Sonya Massey, an unarmed Black woman, in her home by a sheriff's deputy who had responded to her call for help.

Gov. JB Pritzker on Tuesday signed the legislation, which requires disclosure of everything from job performance reports to nonpublic settlement agreements. It resulted from indiscretions that came to light in the background of Sean Grayson, the ex-sheriff's deputy charged with first-degree murder in the case.

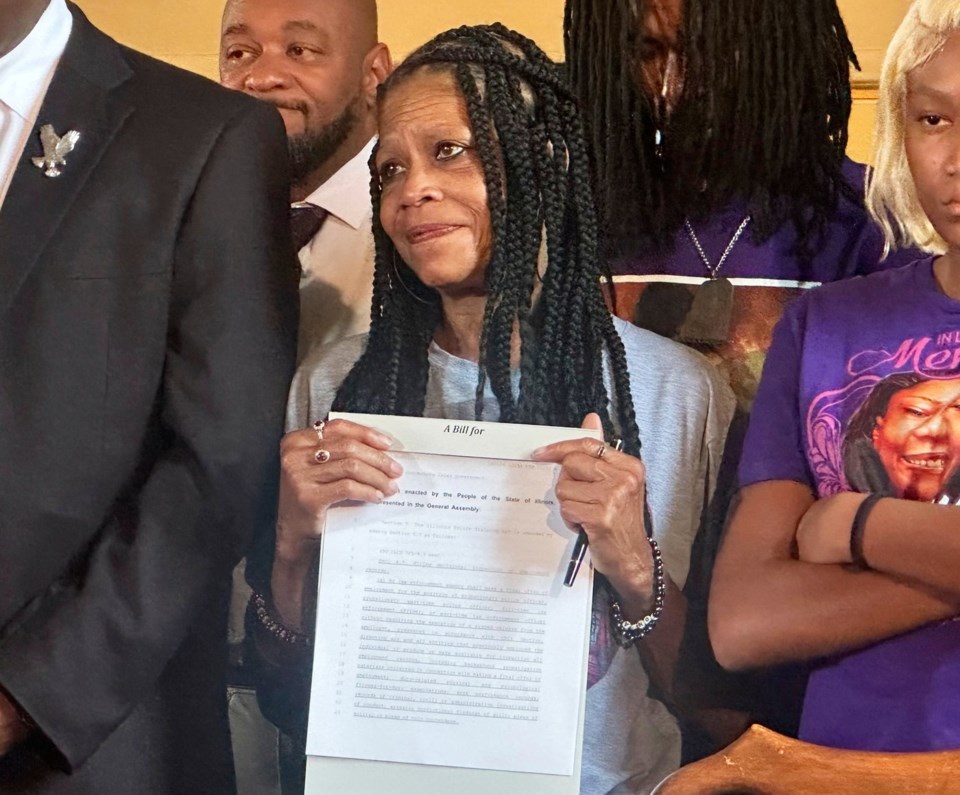

Pritzker, surrounded by Massey's family in the state Capitol, said the first-in-the-nation law should serve as an example for other states as he let Massey's “spirit guide us to action.”

“Our justice system needs to be built on trust,” the Democrat said. “Communities should be able to trust that when they call the police to their home, the responding officer will be well-trained and without a history of bias or misconduct, and police officers should be able to trust that they are serving alongside responsible and capable individuals.”

The legislation was sponsored by Sen. Doris Turner, a Springfield Democrat and friend of the Masseys, and Chicago Democratic Rep. Kam Buckner, who noted that Thursday marks the 117th anniversary of the three-day Race Riot in Springfield that led to the founding a year later of the NAACP.

Who is Sonya Massey?

Massey, 36, was a single mother of two teenagers who had a strong religious faith and struggled with mental health issues. In the early morning of July 6, 2024, she called 911 to report a suspected prowler outside her home in the capital city of Springfield, 201 miles (343 kilometers) southwest of Chicago.

Grayson and another deputy searched but found no one. Inside Massey's house, confusion over a pot of hot water Massey picked up and her curious response to Grayson — “I rebuke you in the name of Jesus” — which the deputy said he took to mean she wanted to kill him, prompted him to fire on Massey, hitting her right below the eye.

What prompted the legislation?

The 31-year-old Grayson was 14 months into his career as a Sangamon County Sheriff’s deputy when he answered Massey's call. His arrest two weeks later prompted an examination of his record, which showed several trouble spots.

In his early 20s, he was convicted of driving under the influence twice within a year, the first of which got him kicked out of the Army. He had four law enforcement jobs — mostly part-time — in six years. One past employer noted that he was sloppy in handling evidence and called him a braggart. Others said he was impulsive.

What does the law require?

Those seeking policing jobs must sign a waiver allowing past employers to release unredacted background materials, including job performance reports, physical and psychological fitness-for-duty reports, civil and criminal court records, and, even otherwise nonpublic documents such as nondisclosure or separation agreements.

“It isn’t punitive to any police officer. The same kind of commonsense legislation needs to be done nationwide,” James Wilburn, Massey’s father, said. “People should not be able to go from department to department and their records not follow them.”

The hiring agency may see the contents of documents sealed by court order by getting a judge's approval, and court action is available to compel a former employer to hand over records.

“Several departments need to pick up their game and implement new procedures, but what’s listed here (in the law) is what should be minimally done in a background check,” said Kenny Winslow, executive director of the Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police, who helped negotiate the proposal.

Would the law have prevented Grayson's hiring?

Ironically, no. Most of what was revealed about Grayson after his arrest was known to Sangamon County Sheriff Jack Campbell, who was forced to retire early because of the incident. Campbell was aware of Grayson's shortcomings and, as a result, made him repeat the state's 16-week police training course.

Even an incident that didn't surface until six weeks after the shooting — a dash-cam video of Grayson, working as a deputy in a nearby county, ignoring an order to halt a high-speed chase and then hitting a deer with his squad car — would not have disqualified him, Campbell said at the time.

“We can't decide who they do or don't hire, but what we can do is put some parameters in place so that the information will be there and the right decision can be made,” Buckner said.

What's next?

Grayson, who also faces charges of aggravated battery with a firearm and official misconduct, has pleaded not guilty and is scheduled to go to trial in October.

Publicity persuaded Judge Ryan Cadagin to move the proceeding from Springfield to Peoria, 73 miles (117 kilometers) to the north. The incident has garnered international news coverage, prompted activists' rallies, and led to a $10 million civil court settlement.

John O'connor, The Associated Press