NEW YORK — The legendary Live Aid concerts 35 years ago did a lot of good — helping reduce African famine and putting a spotlight on the world’s poorest nations. But it wasn't always good for one of its key organizers.

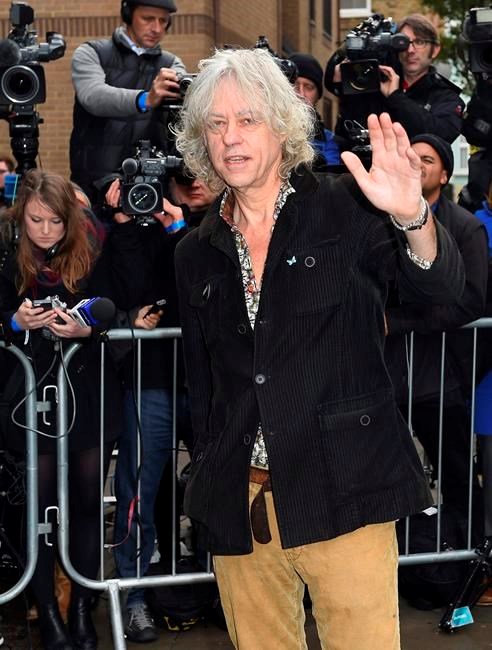

Irish rock star Bob Geldof may have earned awards and cheers for pulling off 1985's transcontinental music event, though it took a toll on his personal life and career.

Live Aid changed Geldof from frontman of the Boomtown Rats singing their hit “I Don’t Like Mondays” to something more divine. “I became Saint Bob,” Geldof told The Associated Press in an interview earlier this year.

He said he wasn’t happy about the glory that came with his charity work. “I hated it. It became impossible,” Geldof said. “For a while I was bewildered. I didn’t have much money at the time. It impinged entirely on my private life. It probably ended up costing me my marriage.”

The whole thing began with Band Aid, an all-star group in the U.K. organized by Geldof and recording artist Midge Ure that included Bono, Phil Collins, George Michael and numerous others on the 1984 single, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” with proceeds going to Ethiopian famine relief.

Geldof then appeared on follow-up American version, “We Are the World” in 1985. Later that summer, he helped organize Live Aid, the most ambitious global television event of its time.

He suddenly found himself an unlikely celebrity.

“It wasn’t because of my superior musical excellence, like Elvis or the Beatles," Geldof said. "Billions of people made me the man of the hour.”

The Live Aid concerts held in London and Philadelphia raised over $100 million. Those shows included performances by Queen, U2, Led Zeppelin, Madonna, and dozens of others. Twenty years later, he hosted the Live 8 concerts and got the industrialized nations to pledge an increase in aid to Africa by $25 billion.

While Geldof’s altruism helped make the world a little better, he said he was no longer able to do what he loved: play music.

“I wasn’t allowed go back to my job. I’m a pop singer. That’s literally how I make my money. That’s my job. I get up in the morning, if I’m in the mood. I’ll try and write tunes. I’ll go and try and rehearse," he said. "And I couldn’t. And no one was interested. Saint Bob, which I was called, wasn’t allowed to do this anymore because it’s so petty and so meaningless. So, I was lost.”

Geldof is glad he and his fellow musicians pulled off their activist concerts because he doesn’t believe the world is the same today as it was during the time of Live Aid or even Live 8.

“It was the end of that political period of

Earlier this year, Geldof finally got back to music and released a new album with the Boomtown Rats, “Citizens of Boomtown,” their first album since 1984's “In the Long Grass.”

Thirty-five years after Live Aid, Geldof remains humbled by his accomplishments, and proud he’s followed a tradition of activist-musicians, like Woody Guthrie, who Geldof cites as one of the main influences of the Boomtown Rats, a band that started during one of Ireland’s most tumultuous times.

“We made a series of records, which became hits – which, of course, helped to change the country a bit. It helped to change music. And then through Band Aid and Live Aid we helped to change the world a little bit, and then we stopped.”

___

Follow John Carucci at http://www.twitter.com/jacarucci

John Carucci, The Associated Press