LA CUMBRE, Bolivia (AP) — Neyza Hurtado was 3 years old when she was struck by lightning. Forty years later, sitting next to a bonfire on a 13,700-foot (4,175-meter) mountain, her scarred forehead makes her proud.

“I am the lightning,” she said. “When it hit me, I became wise and a seer. That’s what we masters are.”

Hundreds of people in Bolivia hire Andean spiritual guides like Hurtado to perform rituals every August, the month of “Pachamama,” or Mother Earth, according to the worldview of the Aymara, an Indigenous people of the region.

Pachamama’s devotees believe that she awakens hungry and thirsty after the dry season. To honor her and express gratitude for her blessings, they make offerings at home, in their crop fields and on the peaks of Bolivian mountains.

“We come here every August to follow in the footsteps of our elders,” said Santos Monasterios, who hired Hurtado for a Pachamama ritual on a site called La Cumbre, about 8 miles (13 kilometers) from the capital city of La Paz. “We ask for good health and work.”

Honoring Mother Earth

Offerings made to Pachamama are known as “mesitas” (or “little tables”). Depending on each family’s wishes, masters like Hurtado prepare one mesita per family or per person.

Mesitas are made of wooden logs. On top of them, each master places sweets, grains, coca leaves and small objects representing wealth, protection and good health. Occasionally, llama or piglet fetuses are also offered.

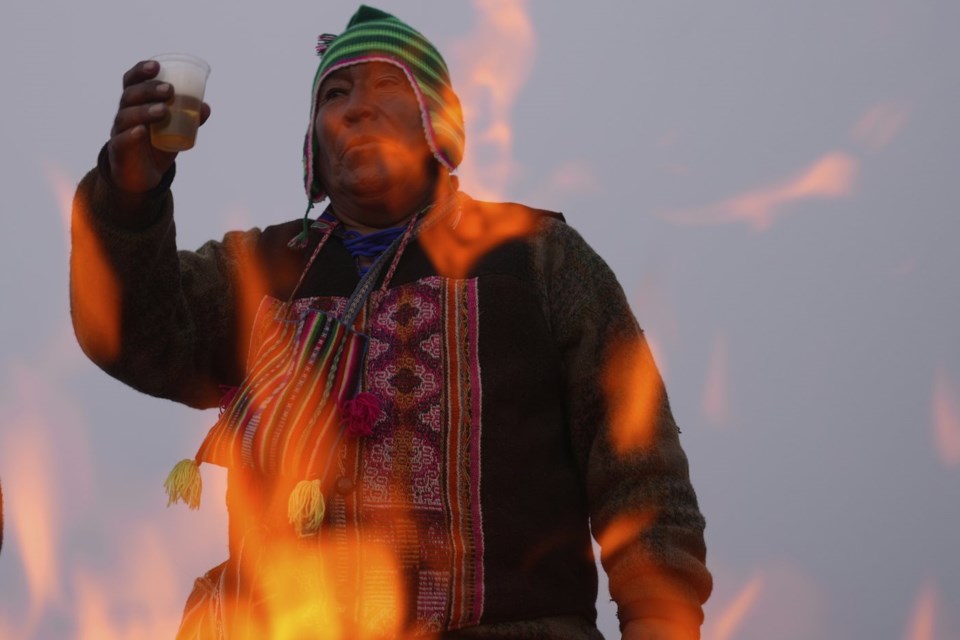

Once the mesita is ready, the spiritual guide sets it on fire and devotees douse their offerings with wine or beer, to quench Pachamama’s thirst.

“When you make this ritual, you feel relieved,” Monasterios said. “I believe in this, so I will keep sharing a drink with Pachamama.”

It can take up to three hours for a mesita to burn. Once the offerings have turned to ash, the devotees gather and solemnly bury the remains to become one with Mother Earth.

Why Bolivians make offerings to Pachamama

Carla Chumacero, who travelled to La Cumbre last week with her parents and a sister, requested four mesitas from her longtime spiritual guide.

“Mother Earth demands this from us, so we provide,” the 28-year-old said.

According to Chumacero, how they become aware of Pachamama’s needs is hard to explain. “We just know it; it’s a feeling,” she said. “Many people go through a lot — accidents, trouble within families — and that’s when we realize that we need to present her with something, because she has given us so much and she can take it back.”

María Ceballos, 34, did not inherit her devotion from her family, but from co-workers at the gold mine where she earns a living.

“We make offerings because our work is risky,” Ceballos said. “We use heavy machinery and we travel often, so we entrust ourselves to Pachamama.”

A ritual rooted in time and climate

The exact origin of the Pachamama rituals is difficult to determine, but according to Bolivian anthropologist Milton Eyzaguirre, they are an ancestral tradition dating back to 6,000 B.C.

As the first South American settlers came into the region, they faced soil and climate conditions that differed from those in the northernmost parts of the planet, where winter begins in December. In Bolivia, as in other Southern Hemisphere countries, winter runs from June to September.

“Here, the cold weather is rather dry,” Eyzaguirre said. “Based on that, there is a particular behavior in relation to Pachamama.”

Mother Earth is believed to be asleep throughout August. Her devotees wish for her to regain her strength and bolster their sowing, which usually begins in October and November. A few months later, when the crops are harvested in February, further rituals are performed.

“These dates are key because it’s when the relationship between humans and Pachamama is reactivated,” Eyzaguirre said.

“Elsewhere it might be believed that the land is a consumer good,” he added. “But here there’s an equilibrium: You have to treat Pachamama because she will provide for you.”

Bolivians’ connection to their land

August rituals honor not only Pachamama, but also the mountains or “apus,” considered protective spirits for the Aymara and Quechua people.

“Under the Andean perspective, all elements of nature have a soul,” Eyzaguirre said. “We call that ‘Ajayu,’ which means they have a spiritual component.”

For many Bolivians, wind, fire, and water are considered spirits, and the apus are perceived as ancestors. This is why many cemeteries are located in the highlands and why Pachamama rituals are performed at sites like La Cumbre.

“The apus protect us and keep an eye on us,” said Rosendo Choque, who has been a spiritual guide or “yatiri” for 40 years.

He, like Hurtado, said that only a few select people can do they job. Before becoming masters, it is essential that they acquire special skills and ask Pachamama’s permission to perform rituals in her honor.

“I acquired my knowledge little by little,” Choque said. “But I now have the permission to do this job and coca leaves speak to me.”

Hurtado said she mostly inherited her knowledge from her grandmother, who was also a yatiri and witnessed how she survived the lightning strike.

“For me, she is the holiest person, the one who made me what I am,” Hurtado said.

She said she finds comfort in helping her clients secure a good future, but her close relationship with Pachamama brings her the deepest joy.

“We respect her because she is Mother Earth,” Hurtado said. “We live in her.”

____

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

María Teresa Hernández, The Associated Press