In a 2004 episode of The Simpsons, Lisa starts a newspaper to challenge a "bigshot" who has just published a newspaper—a contentious one—in their hometown of Springfield.

Mr. Bigshot is a thinly-veiled Rupert Murdoch. Yep, that Rupert Murdoch. The real-life chairman and head of News Corp., which owns so many newspapers and media outlets, including the dubious Fox News, that he makes the term "press baron" seem woefully inadequate.

But the eternally eight-year-old Lisa is unphased. Who cares how big Mr. Bigshot is? (Interesting: the show was actually created for Fox Broadcasting when the real Murdoch still owned it.)

So Lisa gets her hands on a Gestetner—an old-school stencil duplicating machine widely used throughout the 20th century that you crank by hand, something like a mimeograph machine. And she's off to the races in the Simpsons’ garage, cranking out The Red Dress Press, her own little newspaper, on 8 1/2 x 11 sheets of paper. It quickly outruns and outguns Mr. Bigshot's news effort.

Timing in life is everything, and I couldn't have come up with a more amazing coincidence if I'd invented it myself. The show aired on MUCH TV March 11 this year—one day after Paul Burrows died.

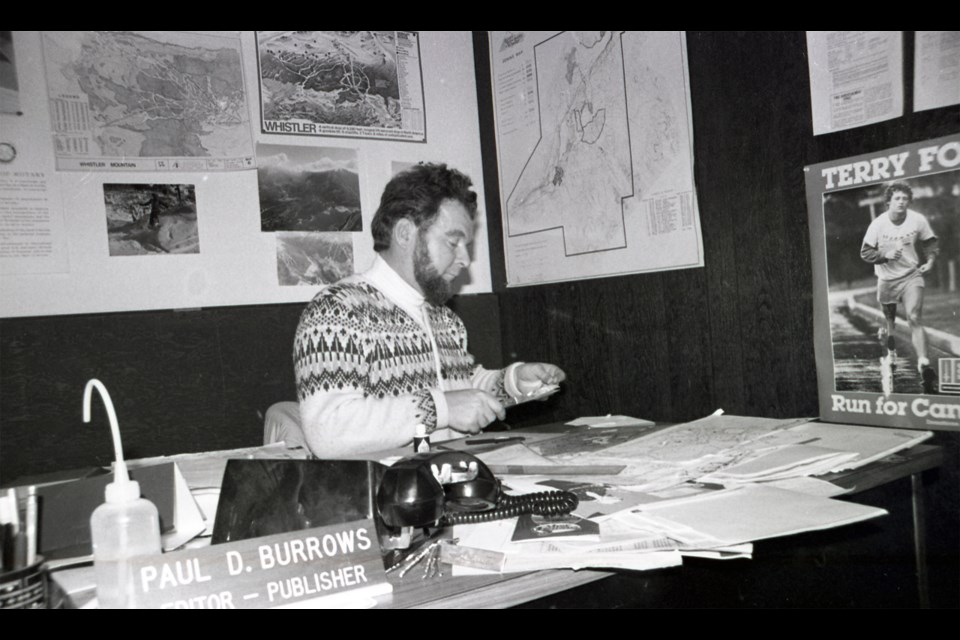

If you don't know who Burrows is, check out Pique's March 26 feature on him here. But for these purposes, let's just say by way of shorthand that Paul was a force of nature who profoundly shaped the trajectory of Whistler. He started Whistler's first real newspaper; sat on council for years; led the first ski patrol; helped start Whistler Search and Rescue; and, overall, impacted so many aspects of the resort community that his personal story mirrors Whistler itself. However, it's his impulse to start a newspaper that we're primarily interested in this go round.

Shortly after he made an unsuccessful bid in 1975 to become Whistler's first mayor, Paul and his wife, Jane, started The Whistler Question, cranking it out by hand on—you guessed it—a Gestetner. And while he never said as much directly, Burrows often implied that one of his reasons for starting it was just in case any local bigshots got too big for their britches.

I wish I could also tell you they produced it from their garage, like Lisa. Close, but not quite: It was all churned out from the basement of their tiny A-frame cabin in Alpine Meadows, which was so small people used to joke about it.

On another thrifty note, the Burrows also chose to start up a newspaper because the only other idea for a new business at Whistler they seriously entertained after Paul wasn't elected mayor was to start a bus line. They came up with an obvious name that made him light up whenever he said it: Burrows Busses. But as you can imagine, buying a Gestetner was way cheaper than investing in a fleet of busses, so a newspaper it was.

As for the paper's unlikely name, The Whistler Question, Paul explained how it arose from the fact that a huge existential question hung over the entire place at the time: Would Whistler survive? Would it make it?

The Whistler Question name was also perfect, as the newspaper, and curious Paul, asked so many questions. Some of them were genuine questions intended to dig out the truth, or the best available version thereof, including what Paul needed to know—but couldn't or wouldn't print—to push things forward in the best possible way. And sometimes they were more rhetorical questions or provocations meant to prod and poke people into thinking better, doing better.

The name proved to be fertile ground on many levels. In a 1977 issue of Garibaldi's Whistler News—the little paper put out by Garibaldi Lifts Ltd., which started in 1964 to build and operate the first lifts on Whistler Mountain—Jenny Busdon recognized The Whistler Question as "the answer" to the local communication problem. Obviously playing on the Question in more ways than one, The Whistler Answer also appeared in 1977—a spunky alternative publication created by Charlie Doyle and company.

If you visit Whistler Museum, you can leaf through a genuine local artifact: A copy of the first edition of The Whistler Question, produced April 14, 1976—one week after Paul's 39th birthday. Printed on both sides of two sheets of legal-sized paper, and stapled in one corner, it cost 15 cents.

It also neatly illustrates how the Burrows played up the Question's cheeky name at every opportunity in what can only be seen as an amazing exercise in early branding. There's "Out of the Question" for the editorial department and "Question-Aire" for letters to the editor. (Get it? "Airing" your views.) The first letter was a surprisingly serious, well-crafted one from a local icon, the late Al Schmuck, who questioned if council of the day was "supporting the letter or the spirit" of a proposed zoning bylaw. It could have been written yesterday.

That first edition also offered a good mix of sober news, sports, and fun community items, with a sprinkling of ads, including one offering Paul's printing skills, which he'd honed to perfection at London School of Printing right before emigrating to Canada. (It's a little known fact, and one Paul played down, but in Vancouver he was highly regarded for his printing skills by some of the best printers in the city.)

No matter how humble its origins, The Whistler Question was an official community newspaper, a classification distinguished from the dailies. As the name implies, community newspapers must serve their communities as the newspaper of record, a role Pique took on after the Question closed. That means running police reports, municipal ads—the things that put the record of the community on the record, as it were. Good community newspapers, like the Question, do that for their communities, and more.

"Seeking out stories, capturing [Whistler] in photos... that was a vital piece of communication in those formative years," says Hugh Smythe, who knew Burrows since the ’60s when they were both on Whistler's first pro ski patrol, and who eventually went on to become president of Intrawest Mountain Resorts when it owned Whistler Blackcomb.

"Whistler was really going through a huge change when the village was being built, and Paul and the Question, whether you agreed with them or not, were kind of the glue."

And while some might think otherwise, Burrows' newspapering was respected enough that for years, he sat on the board of the BC Yukon Community Newspaper Association (BCYCNA), the organization that, in 1981, presented the Question the first of its many publishing awards.

"Paul was a pioneer in our industry who epitomized the effort and values that places local journalism at the heart of the community," noted Randy Blair, COO of Black Press Group Ltd. and a long-time member of the BCYCNA, who knew Paul.

Burrows also became an advisor, first to the printing program and later to the journalism program, at Vancouver's Langara College, the only journalism school in Canada west of Toronto at the time.

In fact, it was only because he was an advisor to Langara's j-school, as we call it, that I landed my first job as a cub reporter at the Question. Around the time for me to graduate, Paul had placed a tiny ad on the classroom bulletin board (yes, we actually used a cork bulletin board—and typewriters). I applied, and got the job. Months later, when Paul and Jane asked if I wanted to buy the Question, I bit and became one of the youngest publishers in Canada, and one of the very few women. In fact, my first issue in 1981 was the fifth anniversary edition; the 10th anniversary paper was my last.

Yes, it was long ago by some metrics, and only yesterday, by others. But I just want to put a couple of things in perspective that most people wouldn't know about unless they worked in the industry.

First, just for the record, despite Whistler being a very, very small town at the time, and the Question being even smaller, my experience working there made for an excellent start to my too-long career as an editor and journalist for a range of dynamic clients and topics which also interested Paul: science, art, politics, law.

Burrows played no small part in that. Unshakeable in his values and integrity (after all, he often reminded us, he was trained by Quakers and Jesuits), he was also a prodigious thinker with a broad and informed worldview. He never shied away from questioning the status quo, no matter how much he ruffled feathers, or from going to bat for us staffers when we got in the glue.

The idea of three estates was a traditional European concept: the "three classical estates of the realm." The clergy was the first estate; the nobility, second; and the so-called "commoners" the third. In 1841, Thomas Carlyle, a British essayist, historian, and philosopher who was a leading writer of the Victorian era, coined the term "fourth estate" for the press gallery in British Parliament, something "more important far" than Parliament itself. The fourth "estate" was regarded as one unto itself, meant to independently challenge the rest of society. That's what Paul, and those of us lucky enough to work for and with him, did with verve—sometimes too much of it.

The next "level" was the fifth estate—a term from the ’60s for counterculture outliers, people commenting on society from outside mainstream media. Icons of the day were the influential underground newspaper of 1960s Detroit, The Fifth Estate, or Vancouver's The Georgia Straight. Locally, it was The Whistler Answer. Today it might be a blogger.

On a more feminist counterculture line, keep in mind that 99 per cent of newsrooms throughout history were run by men. With a few rare and welcome exceptions, they could also be living hells for women, even as late as the ’80s. They still can be today.

I've known many a female journalist who either quit or suffered a breakdown due to the sexist treatment they endured in a newsroom. By contrast, Paul was totally fair with women and treated us as equals. More than one person joked that he'd have to be to have married Jane, who was as strong as they came. But it went beyond that.

For instance, he was furious when he learned that Whistler's local Rotary Club of the early ’80s—in fact all Rotary Clubs of the day—wouldn't accept me as a member, even after I'd bought the newspaper, simply because I was a woman. That didn't change in Rotary until 1989, but the unlikely notion of such discrimination had never even crossed Paul's mind.

Burrows and The Whistler Question also kickstarted numerous other publications, including Whistler Magazine, as well as the careers of a lot of other rookies—another legacy he could be rightfully proud of. He had a knack for attracting talent, then he trusted you and gave you free rein. Anita Webster became a successful public relations consultant. Craig Spence and Mick Maloney both went on to become editors of the sadly defunct Vancouver Courier. Stewart Muir rose to deputy managing editor of the Vancouver Sun, where Kevin Griffin also worked for decades as one of its finest reporters. As for Geoff Olson, he quickly abandoned his haphazard career as a delivery boy and went on to become a sought-after editorial cartoonist and writer (see below).

The other seminal thing the Question did was provide the fertile ground that this publication, Pique Newsmagazine, sprang from. Bob Barnett, and his wife, Kathy, honed their skills at the Question for years before going on to start Pique in 1994; Bob, as a Question reporter and editor, and Kathy as the Question's publisher/controller. Happily, Pique is now approaching its 30th anniversary.

With online ad sources like Craigslist, and the internet and social media slurping up huge chunks of ad revenue and readership the past 20 years, newspapers left, right and centre have been closing like there's no tomorrow. In Canada, 250 local newspapers shut down between 2008 and 2018—including the Question, closed in 2018 after 41 years. One American school of journalism estimated last year that two local newspapers are shuttered every week in the U.S.

In light of all of the above, it's even more worthwhile reflecting on Paul's legacy in terms of The Whistler Question, not only because he died recently, but because the newspaper was so much larger than the sum of its parts.

Sure, it began on an entrepreneurial whim on two sheets of paper, stapled in one corner, but the Question quickly established itself as Whistler's respected newspaper of record, an invaluable contributor to the history of the resort and to the public discourse that shaped it. What kind of a place would it be? How would it evolve? Who would it attract? What would its guiding principles and values be? What would have changed had there been no Paul or no Question?

It also provided a strong, healthy newsroom and public platform for those of us lucky enough to work there, especially since for so many of us—including me and pretty much every person who has submitted a story below—it was our first job newspapering.

At some point, the cheeky in-house nickname "Questionables" evolved for anyone who worked at the Question, no matter where our paths took us. It was a badge of honour.

What follows are some very Questionable stories.

We. Are. Family.

“Even though Paul and Jane Burrows didn’t have biological children of their own, they sure did care for a wide spectrum of Whistler youngsters. Jane, as one of Whistler’s first and longest-serving kindergarten teachers, helped foster good, life-long skills in the lives of many five-year-olds. Paul, on the other hand, had children of a different sort to deal with: his employees.

The Whistler Question was our family, albeit a dysfunctional one at times. We were young and away from home, and Paul and Jane took care of us. This is just one story that illustrates that—a tale of human failings and taking the path of least resistance.

In the early ’80s, my ’64 VW Beetle died on the highway as I was driving up from Squamish. Apparently, the gas station attendant (remember those?) had left a rag on the fan housing after checking the oil. By the time I was climbing Power Line Hill, the poor thing stopped “breathing” and sputtered to a stop.

=After returning to work and relating my tearful tale of woe, Paul took things in hand. He drove me back and helped me strip the thing bare, licence plates and all. We abandoned the car—together—on the side of Highway 99. I confess, yes, it was not the right thing to do and quite irresponsible. No excuse now, but at the time Paul did his best to help me, bless his heart.”

-Pauline Wiebe (nee LePatourel), Questionable typesetter and receptionist

Yabbering in Swahili? In Whistler?

“A month after I arrived in Whistler in 1980, having just emigrated from Kenya, I saw an ad in The Whistler Question looking for a typesetter. I ran up to their office, above where Southside Diner is now in Creekside, and left my resume. A few hours later, I got this phone call and there's this person yabbering at me at full speed in Swahili, telling me I was starting work tomorrow. I spoke Swahili having grown up in Kenya, which was on my resume, and Paul still remembered Swahili from his years in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The job was using an IBM Electronic Selectric Composer to typeset the newspaper, which I'd actually had huge experience on, including writing IBM Africa's manual for it, so Paul was all excited.”

-Shayne le Poer Trench, Questionable typesetter

No pretending it's not a pretense

“One day, a guy came into the office wearing a distinctive hat and when he left, Paul said, ‘Do you think that hat keeps him warm, or is it just affectation like mine?’”

-Anita Webster, Questionable receptionist, "thumper," reporter, assistant editor

On the advice of my lawyer...

“In 1981, when I was loafing away the summer in the South Okanagan, I was looking for a little more excitement and phoned up my journalism school buddy, Glenda Bartosh, who'd secured her first job at The Whistler Question.

It was a time when a major evening's entertainment was watching the bears forage at the town dump, the village centre was under construction, and the mayor moonlighted as a coffee salesman.

In keeping with the mercurial pace of the town’s development, which included hosting a World Cup race during my short tenure, Glenda had risen from reporter to editor in a few short months, answering to publisher Paul Burrows.

Burrows was a curious figure. It was rumoured he'd drifted into Whistler as an itinerant folksinger. He spoke knowledgeably and with precision in a clipped accent on wide-ranging topics, and wore his beard sans moustache, baring his upper lip like someone who might be involved in a religious sect. If he was a man of faith, it never showed in the four-person Whistler Question office across from the Husky gas station.

My early impression of the new boss was of an affable man constantly on the go. He often left the office to attend to his various duties, which included scarfing up business for his fledgling publication, gossiping with the town's powerbrokers and fending off incursions from rival publisher Cloudsley S. Q. Hoodspith, who ran the Squamish Times and, in Burrows’ assessment, was poaching advertisers from the Question.

He was a trusting boss and gave his blessing to a crude column I started about my sauce-addled life as a bachelor-about-town in Whistler. It’s sophomoric, amateurish name, Maloney’s Mouthpiece, says it all.

My duties had expanded from reporter/paperboy to reporter/columnist/paperboy. The latter job involved the delivery of the paper to various drop-off spots around the valley. Returning in the company pick-up after one such foray, I was directed by Burrows to load up hundreds of copies of a supplement the Question had put out a month previously and discreetly deliver them to the dump, now abandoned by the bears, at least in daylight.

I pulled into the dump furtively, keeping a wary eye out for Cloudsley Hoodspith and hoping no advertiser who paid the full circulation rate for the supplement would catch me offloading the excess papers. I parked beside another vehicle offloading excess uncirculated editions of our local rival, The Whistler Answer. If memory serves me, the individual doing the jettisoning was Answer publisher Charlie Doyle, who graduated from alternative journalism to a life on Whistler’s Easy Street. But that was a long time ago and on the advice of my lawyer, I can’t be sure it was Doyle.

At any rate, Burrows took the news of the dump meeting with good humour. The folksinger turned journalist turned businessman was a pragmatist.”

-Mick Maloney, Questionable reporter/columnist/paperboy/newspaper disposal unit

Taking a flyer in good stride

“One of the jobs Paul delegated was taking the Question’s proceeds from ad and newsstand sales from the office, then located on the second floor of Southside Lodge at the Gondola side of Whistler, to deposit at the bank in Pemberton every Thursday, which was when we also delivered the newspapers destined for the town's newsstands. For a short time, he entrusted this critical task to Geoff Olson, our editorial cartoonist and occasional illustrator.

On this particular day, the company pick-up truck was parked out front and, as fate would have it, we were all watching out the window from the second floor as our would-be courier headed on his way.

The newspapers were already safely stowed in the back of the truck. As for the bank deposit, it was already tallied in a small deposit book which, along with bills, coins and cheques, was all put in a flat, shallow cardboard box with no lid to make it easy to carry to the bank.

So we were all watching as Geoff placed the box on the truck roof since he needed both hands to open the door. I remember being somewhat concerned, lest a gust of wind suddenly blow the cash and cheques, or the entire box itself, off the roof. But Paul didn’t seem at all fazed by this possibility. Sure enough, when Geoff got into the truck and slammed the door, the contents remained undisturbed. And still on the roof!

‘No!’ I thought out loud, anticipating what was about to happen. But amazingly, Geoff managed to back out, point the truck up Lake Placid Road toward the highway, and take off without anything being ruffled in the least. Cries from his colleagues up above, of course, went unheard.

Then Geoff drove off at his usual clip—with the cheques, bills and everything else fluttering in his wake when the box finally flew off the roof as he turned onto Highway 99. We were awestruck. Paul, however, took it all in stride. As I recollect, he simply shook his head with a knowing smile which said, maybe depositing our weekly earnings isn’t Geoff’s strong suit.”

-Craig Spence, Questionable reporter

A blur of green lips

“I have two strong memories or reflections about Paul.

The first was when I was looking back through early issues of the Question for the newspaper's 15th-anniversary issue we did. Sitting in the office overlooking Village Square and all the activity in the village, circa 1991, and reviewing stories about the original proposals for Whistler Village and related issues, I was struck by how Paul's commentary and criticism were spot on.

In 1991, it was easy to see how proposals such as the one to build a village of eight square blocks would have been a disaster, but to make those sorts of calls in the 1970s showed a lot of foresight on Paul's part.

My other recollection was maybe less significant, but more Burrowesque.

Paul used to drop by the Question office several times a week in those days (the early ’90s), unannounced, but full of ideas and gossip. The newsroom was comparatively wealthy then, with four, maybe five of us, each with a desk along the perimeter walls.

One day Paul came in directly from skiing. He was wearing a one-piece ski suit, maroon red, I think, with lime green flashes on the pockets. He was also wearing matching lime green sun protector on his lips. And his lips were moving at full speed as he came into the newsroom, pontificating about something.

He did a full lap of the newsroom, looking over each reporter's shoulder, talking non-stop the whole time, and then he exited—only to be struck by another thought in the reception area which propelled him to return for a second lap of the newsroom, lime green lips moving the whole time.

When he left, there was a moment of stunned silence in the office, and a little green glow.”

-Bob Barnett, Question reporter and editor, May 1989 to 1994, when he and his wife, Kathy Barnett, the Question's publisher/controller, left to start Pique Newsmagazine

Maxed out appreciation

“I've lauded Paul in the past for his contribution to the public record. Having written a number of Whistler history stories, I'm in his debt for having started and kept the Question going. Trying to dig out the pre-Question history of Whistler is a frustrating exercise. Everyone has a different version of the same event. As sketchy—and banal—as the Question often was, it remains the best objective record of things that happened in town from its inception until Pique found its stride. The town owes Paul a debt of gratitude for his work.”

-G. D. "Max" Maxwell, Pique columnist since 1995

Glenda Bartosh is an award-winning journalist who thinks we all need to pay way more attention to the importance of good solid media, and what happens when it's gone.

Celebration of life in Whistler on May 13

A private graveside service will be held at 11 a.m. on Saturday, May 13, when Paul will be placed alongside his dear Jane. A celebration of life will follow at 2 p.m. in the Millar Room of the Myrtle Philip Community School, located at 6195 Lorimer Road. Starting at 1:30 p.m., you can connect via Zoom at whistlermuseum.org/burrows.

Paul and Jane's preferred recipient for donations is the Whistler Museum & Archives Society.

Messages of condolence can be left at bowersfuneralservice.com.