Go ahead, I dare you. Take a deep dive into your fridge and see what you find.

Sure, there’s probably some pretty good-looking stuff up front or “on top,” as it were, of the produce and meat drawers. Maybe milk; some hummus; fresh veggies; a half-bottle of salad dressing or three; some chicken. But dig a little deeper, a little further back, and what do you find lurking?

That sad, anonymous container stuffed with indecipherable leftovers sporting a fuzzy grey topcoat that should be donated to a biology lab? Some slimy lettuce that got away on you? A jar of something-or-other—tamarind paste?—years after its best-before date, something you know no one will ever use but can’t throw out, regretting why you never used it up while it was still good.

Well, the jury is in—yet again, folks—and we humans are wasting more food than ever. The 2021 UN Environment Programme’s Food Waste Index—aimed at sustainable development—is out, and it reinforces we’ve still got things wrong.

Some 17 per cent of all the food we produce on this beautiful planet is wasted, even more than anticipated. It’s rotted, trashed, dumped, destroyed—in fields and on the hoof; in trucks before it ever reaches a shelf; in stores and warehouses once it arrives (just check the dumpsters outside one day); in the nooks and neglected crannies of our own fridges and shelves; in restaurants and school cafeterias.

It all adds up to more than 1 billion tons of food wasted each year. And the lion’s share of food waste—61 per cent—happens right at home. Retailers, by comparison, account for 13 per cent.

We Canucks are pretty bad offenders. At the household level, the average Canadian wastes 79 kilograms of food annually, or about 175 pounds.

Think of it! That’s the weight of a full-sized human adult, gone, wasted—in only one year, and that’s per person! Imagine if you had a 79-kg uncle living with you and you gradually started chipping away, “losing” a bit of him here and there, until finally he’s gone at the end of the year. Then another uncle or aunt moves in with you, and on it goes, year after year. Next thing you know you don’t have anyone asking to stay at your place (insert winking emoji). But seriously, think about it, including my irreverent metaphor bringing it all home, so to speak.

Surprisingly, when it comes to household food waste, we Canadians outrank our U.S. neighbours. The average American wastes 59 kg annually at the household level. Another 64 kg per capita are wasted in food service, and 16 kg per capita at the retail level. (Sorry, no UN stats are available for Canada in these last two categories.)

That means each of us—since we all eat food, right?—holds a fair chunk of our changing climate and the future of our only home planet right at home in our kitchens.

I like how UNEP’s executive director Inger Andersen puts it: “If food loss and waste were a country, it would be the third biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions,” she wrote in this recent UN report.

Luckily, in the Sea to Sky, we have some brilliant young people chipping away at food waste and the climate crisis.

This Friday, March 19, Fridays for Future—which arose from Greta Thunberg’s student strikes in 2018—is once again organizing a climate-action strike to remind us all we’re still a dangerously long way from the Paris Accord climate targets.

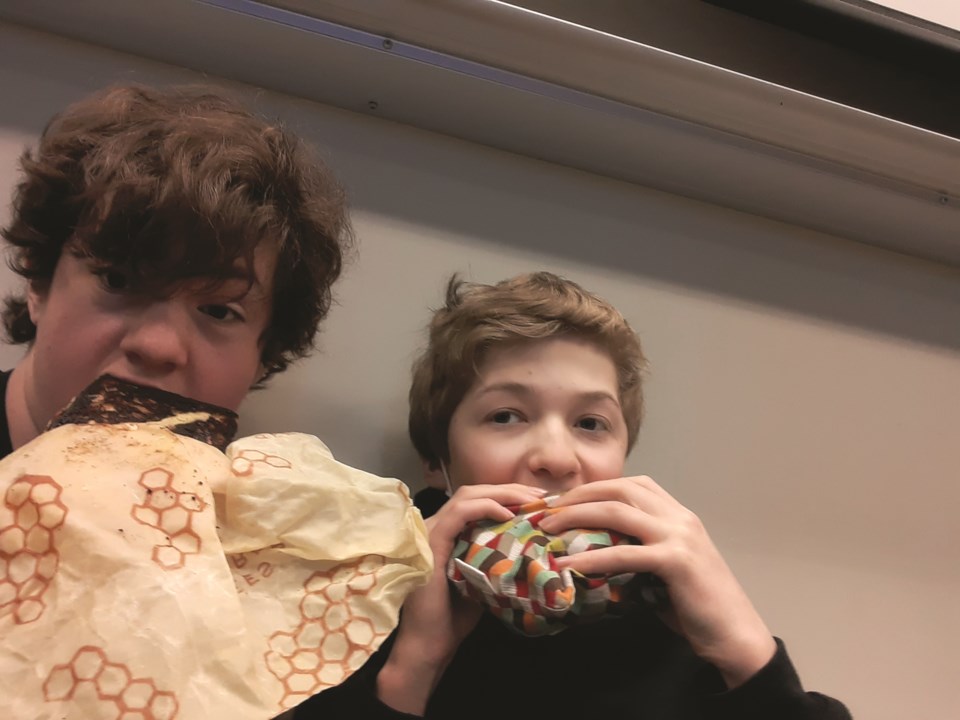

To support the action strike, Pemberton Secondary eighth-grader Sam Tierney and his good friend and classmate, Patrick Tarling, have come up with a cool project for their humanities class. The project had to create social change, and while Sam and Patrick wanted to do something for March 19, COVID-19 meant they had to get innovative, since nobody can gather for a March march.

After learning that Pemberton is developing its first climate-action plan, Sam and Patrick put a “suggestion box” in the school’s front office to gather ideas for the plan that reflect “the voice of the student body.” After summarizing the suggestions, Sam intends to present them to Pemberton’s mayor, Mike Richman, on March 19 along with a petition urging council to adopt the ideas.

While there’s a rich range of suggestions—from having more frequent bus service to educational campaigns about eating locally and in-season—about one third of them address food and related waste, such as feeding your dog food scraps if you can’t compost them, or replacing plastic wrap with beeswax food wrappers.

“I’m excited to see where this all goes,” says Sam. “I think the fact that Pemberton is making a climate-action plan is really good… We’re just a small town who want to do as good as we possibly can.”

As for incorporating students’ ideas into the local climate-action plan, “I think it’s important because we may have different ideas and different ways of looking at things than adults that they might not have thought of,” he says.

“I think we have every right to be taken just as seriously as the adults because we are the future.”

Hey, readers! Sam and Patrick encourage you to get outside March 19 and do something in nature you love or show what you appreciate and is worth fighting for. Post a photo of either with the hashtags #thisiswhatwearefightingfor and #nomoreemptypromises. Tag @powcanada and @FridaysforFuture.

Glenda Bartosh is an award-winning journalist who tips her hat to good teachers like Joanna Williams and Steve Evans at Pemberton Secondary for guiding our “students for future” in the right direction.