In film studies, we learn about the "gaze" - the idea that all constructs are moulded to fit the dominant gaze and aren't authentic or truthful representations.

Much the same could be said of the way Canada's First Nations are represented. We may feel that we're getting sensitive depictions in films like The New World, Avatar and Dances with Wolves , but even those constructs have burst forth from a dominant, westernized gaze. Whether out of ignorance or inaccessibility, authentic representations of First Nations often elude us.

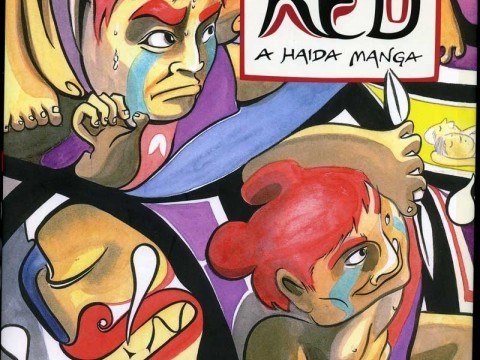

There are few ways to escape this situation, but graphic novels may hold the answer. I believe that's what Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas is trying to do with Red: A Haida Manga, an innovative but confusing foray into comic art.

Yahgulanaas, a Haida artist and son of a fisherman, was exposed to Japanese culture at a young age. He was drawn to manga because it has no roots in settler culture, unlike the styles you find in D.C. or Marvel Comics, he once wrote in Geist Magazine. He was equally drawn to the art because it has some roots in the north Pacific region.

His aim, as he tells it himself, is to get away from stereotypes such as the "wooden Indian, the abandoned village, the romantic image of the vanishing people." In short, escape the gaze that's been foisted on him.

Yahgulanaas tries to achieve this through a beautiful tapestry that spans 108 pages. It tells the story of Red, a young boy who grows up to become leader of a village in the Pacific Northwest. Growing up in a village called Kiokaathli, he's a reckless child, a constant worry for older sister Jaada, who always has to save him from trouble.

Red has ambitions to be a shaman and must thus go on a spirit quest. In this society, people are conceived in the ocean, born on the beach and they become adults in the forest. It's while he's on his quest that raiders arrive in Kiokaathli.

Red eludes them after they chase him up a tree but they kidnap Jaada, setting him on a lifelong quest to get her back. His journey to find her takes him to Laanaas, where he sees her but doesn't find exactly what he was looking for.

The look of Red is positively surreal. Lines and curves that look to form part of a greater tapestry separate cells. In the story, based on a traditional oral narrative, humans coexist with animals in a way that can only happen in myth. Raiders coming? No worries. The heroes jump into the blowhole of a killer whale and escape into the sea.

Then, among the raiders themselves, you find a warrior who looks to be a hybrid of a demon-child and a shark. Surreal fantasy might be a label that future academics attach to the work. Or magic surrealism. Take your pick.

Like in myth, these eccentricities are the kinds of things you just take in stride if you want to appreciate the whole, always a tough thing to do and that's no less true of Red . The narrative itself is difficult to penetrate and likely makes more sense to people who heard it orally.

Overall it's a beautiful work of art and its mainstream appeal ought to break a new path for First Nation stories to get out beyond their oral origins. I certainly hope they can get there because Canada's First Nations have stories to tell that are best told through their own gazes - not the ones that have been foisted upon them.