A new rehabilitation project is currently underway to help restore parts of the landslide debris field at Capricorn Creek.

Back in 2019, Troy Bikadi, community and workplace health and safety officer with the Lil’wat Nation, connected with Veronica Woodruff, project manager and co-founder of Clear Course Consulting Ltd. about his idea for the area.

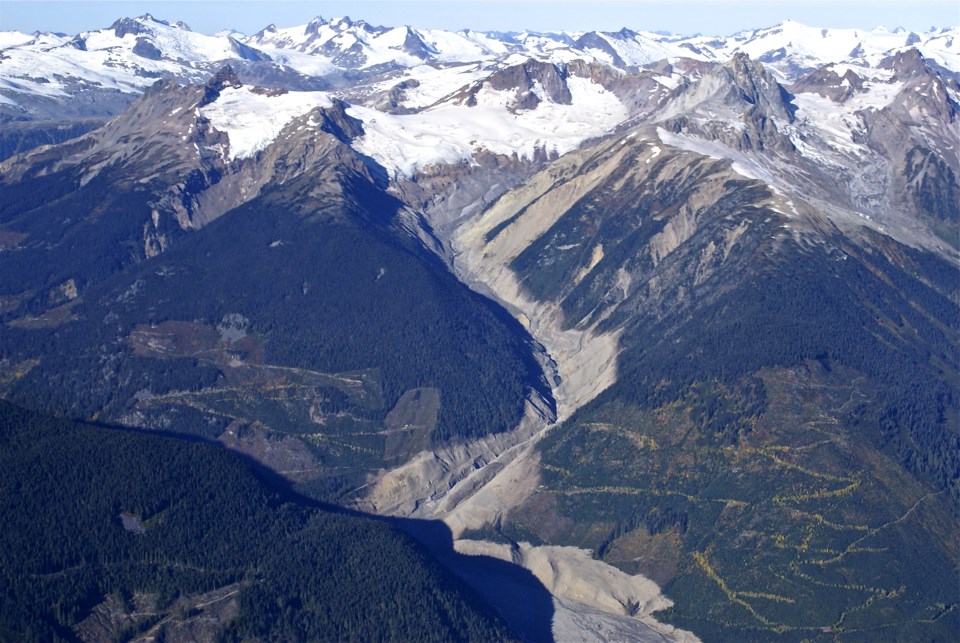

The four-square-kilometre debris field is the result of the 2010 Mount Meager landslide, which sent 50 million cubic metres of debris into the valley below. Virtually a “moonscape,” according to Woodruff, 11 years later, the untouched landscape has fragmented wildlife habitat and increased flood risk.

The pair applied for their first grant through the Habitat Conservation Trust Fund seed funding to develop a proposal and have been working on the project since, Woodruff told Village of Pemberton council at its last meeting on Tuesday, June 1.

“[At] the mouth of the Capricorn Creek and Meager [Creek] … there’s a ton of mobile material sitting there that’s actively moving and eroding into the downstream reaches through freshet and all the storms, winter avalanches, that kind of thing,” she said. “This is the kind of material that we want to start shoring up. There are landscape scale processes that have been done through things like mining and reservoir and reclamation work that we’re modelling our project proposal on.”

With unlimited funding, they could attempt to restore the entire area, but currently the more conservative plan is to create corridors with planted material, Woodruff said in a follow-up interview. That would help animals like bears, wolverines, moose and deer with crossing the massive swath of rocky land.

“We’re going to support the area to generate more quickly [by] augmenting the landscape with topsoil from industry work nearby—logging, mining operations. We can work with those partners to stockpile that topsoil then truck to these sites and incorporate the fungi and soil nutrients into the site,” she said.

This effort would also help with flood risk to the valley. “There’s a lot of material currently mobilized from that site downstream,” she added. “Updated flood mapping says we can anticipate ongoing deposition of material for decades. Anything we can do to stabilize the source of material is a good thing in managing this untenable flood risk.”

There are also implications for fish like coho and chinook, which are found right up to the slide site, so the plan also incorporates habitat improvements along the river.

The plan is to first test a number of plots to see what works well before expanding to the rest of the area, Woodruff said.

Several different agencies and institutions have jumped on board with support—including Pemberton council during the meeting, which offered its support in any way it could—ranging from local governments to the provincial government, including the ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development.

BCIT has also expressed “extreme interest” in making the site their “living lab” for bachelor of science and master of ecological restoration students, as well as for their field diploma skills.

“The project aligns so well with so many of their programs, they’re pretty excited about this opportunity,” Woodruff said. “This idea of a living lab where you can engage students with the project being led by Lil’wat, supported by government, partnered with NGOs, it has a really good partnership opportunity for their students.”

The project is expected to be rolled out over 10 years. If funding comes through, work can begin as early as the fall.

“A decade from now, we’ll be able to quantify how many square metres we were able to restore, what was successful and what wasn’t,” Woodruff said. “Because the landscape is challenging and requires machinery to create conditions where plants can grow, we have to test out techniques … A phased approach allows us to test what’s working. In the meantime, we’ll be restoring small pockets at a time and building off pieces that work.”