When a helicopter-pilot friend calls you on a sunny powder day and asks if you want to go heli-skiing, the only answer is “yes.” That was as true four decades ago as it is today.

But when that friend calls and asks if you’re interested in laying down the winter’s first tracks on a newly-cut run? You grab your skis and run out the door.

That unique experience fell into Brian Tutty’s lap on Sunday, Dec. 9, 1979, one year before Blackcomb Mountain’s lifts first opened to the public. It’s one he remembers fondly, even 43 years later.

As Tutty recalled, the skies had just cleared after Whistler’s first big snowfall of the season. “The runs had been cut that summer, but the lifts were being put in next summer,” he explained.

Blackcomb president and general manager Hugh Smythe called his neighbour, Whistler Okanagan Helicopters base pilot Peter McLennan, with a question: could they go skiing?

Smythe told McLennan he wanted “to check out the fall lines,” Tutty remembered. “And Pete said, ‘Well, what are you doing tomorrow?’”

Smythe had laid tracks on Blackcomb’s slopes countless times before, but those runs usually included more bushwhacking than float-y powder turns.

Throughout the winter of 1978-79, Smythe and planner Mike Collins skied through the trees “pretty much every day,” Smythe recalled. “It sounds like it was epic—on a really nice day it was great—but most of them weren’t quite as nice,” he said with a laugh. “On a good day, we’d get about three runs. As it’s not just skiing, it’s, you know, traversing back and forth and looking at the terrain and following some of the mapping that had been done.”

Luckily for Tutty—he and McLennan had recently procured a cabin in White Gold—the pilot had space in the chopper for a few friends. The men headed up with a small group that also included Don Anderson, Brent Wallace, Brian Worth and Nicki Valentine.

“To go up in the chopper, with the first group of public guests was really, really a hoot,” said Smythe.

Long-forgotten photo from memorable day donated to the Whistler Museum

As Valentine remembered, it was a day of “firsts.” Her “First time in a helicopter and first time skiing this new mountain Blackcomb, before anyone had skied it,” she recalled in an email. “I’m not sure which was more exciting.”

She added, “I do remember coming down that last slope, in powder snow, hoping no rocks or slash lurked below, as it was early in the season. And waiting for us, was Peter McLennan, our pilot and friend. Amazing experience, I was very lucky to be included!”

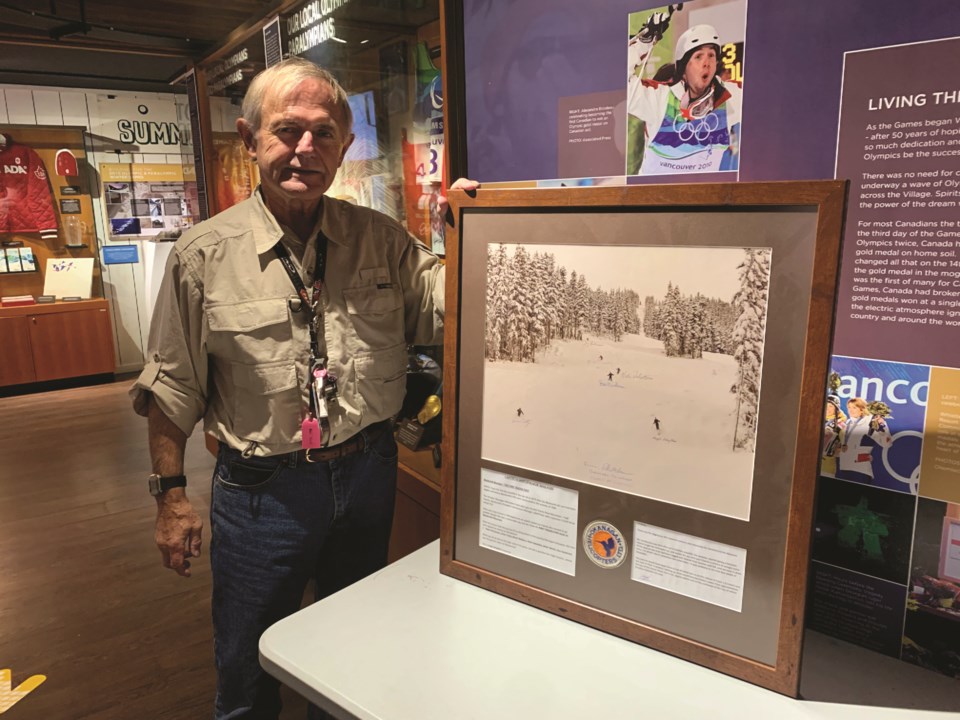

McLennan snapped a photo from the helicopter as the group approached the pickup point, slightly above and to the southeast of where the top of Excalibur Gondola sits today. Tutty donated the photo, signed by the skiers in the frame, to the Whistler Museum on Nov. 17.

For decades, the photo was forgotten in Tutty’s basement in Nanaimo, hidden behind another cherished picture of Black Tusk during sunset. When the glass covering that photo broke, Tutty recovered the treasure. He called his old friend, Valentine, who suggested framing the shot, “and then it evolved from that point,” Tutty said.

“My daughter said, ‘Dad, you’re going to give this away?’ and I said well, I’ll donate it to the museum so others can appreciate it,” said Tutty, adding that he suffered a heart attack earlier this year.

Despite that scare, Tutty’s loaded up with passes for both Whistler Blackcomb and Mount Washington and is looking ahead to another winter on the slopes. “I hope I can keep skiing,” he said. “I’ve been skiing since I was 12.”

Whistler Museum, meanwhile, is “very happy” to add the image to its collection, said curator and executive director Brad Nichols.

“We’re going to preserve this stuff, not for the next five, 10 years, but for hundreds of years down the road," he added. "That’s the whole museum game."