Over the past few months we have received quite a few donations of artifacts and archival records at the Whistler Museum, including scale models, archival films, and photographs in various forms. One recent donation included a copy of a land title of an early 20th-century Alta Lake resident whose name is well known throughout the valley: Harry Horstman.

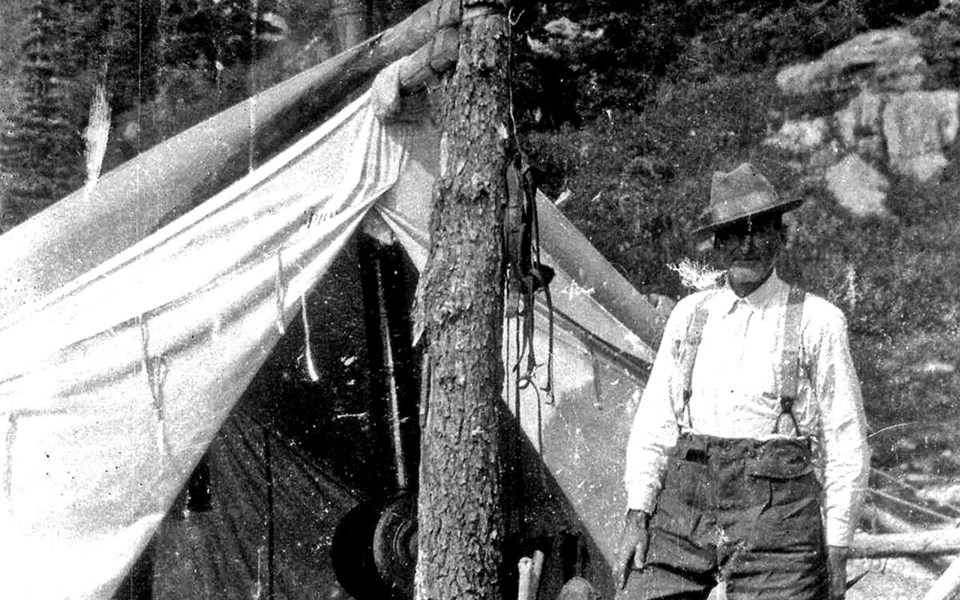

Horstman moved west from Kansas at some point prior to 1912. He staked a mining claim on Mount Sproatt, where he spent much of his time searching for copper and iron (and possibly dreaming of gold). He also preempted two parcels of land, one between Nita and Alpha Lakes and another at the other end of Alpha Lake.

Preemption was a method of acquiring Crown Land from the government for agriculture or settlement; preemption did not take into account Indigenous claims to land, and the land that Horstman preempted is part of the unceded territory of the Squamish Nation and the Lil’wat Nation. According to this recent donation, Horstman’s property at the south end of Alpha Lake was known as Lot 3361 and was made up of 150 acres, more or less.

Horstman kept a small farm on his property near Nita Lake where, according to Jenny Jardine, he had 50 to 60 chickens, “all sorts of potatoes and rhubarb and gorgeous cauliflowers.”

He sold eggs and fresh produce to Rainbow Lodge and other Alta Lake residents to supplement his income from prospecting. Part of his property on Alpha Lake was acquired by Thomas Neiland, who moved to Alta Lake with the Jardine family in 1921 to set up a forestry business. It is not, however, clear how much of the 150 acres was used by Neiland or whether Horstman made use of the rest of the land.

While some Alta Lake residents, such as Jenny Jardine’s brother Jack and railway section foreman Fred Woods, got to know Horstman relatively well, others described him as an “odd man” and may have seen him mostly from a distance. According to Pip Brock, Horstman “didn’t enjoy people that much,” though he was part of the Alta Lake Community Club in the 1920s and was even put in charge of the coffee at their first picnic.

In 1936, Horstman sold his Nita Lake property to Russ Jordan, who reportedly bought the approximately 160 acres for $2,000. When Horstman began to find the physical labour of prospecting too much, he retired to his cabin on Alpha Lake, presumably on his property on the south end of the lake. He remained there until about 1945, when his neighbours on today’s Pine Point, Dr. and Grace Naismith, arranged for Horstman to move to a nursing home in Kamloops.

Harry Horstman died in 1946 and was buried in Kamloops, though his name can still be found throughout Whistler, most notably the Horstman Glacier on Blackcomb Mountain. In an interview in the 1980s, however, Jack Jardine expressed his confusion as to why Horstman’s name was given to a glacier on a mountain Horstman was never known to climb.

For regular updates on what new donations have been made and what the Collections Department is up to, you can subscribe to the Whistler Museum’s bimonthly newsletter. n