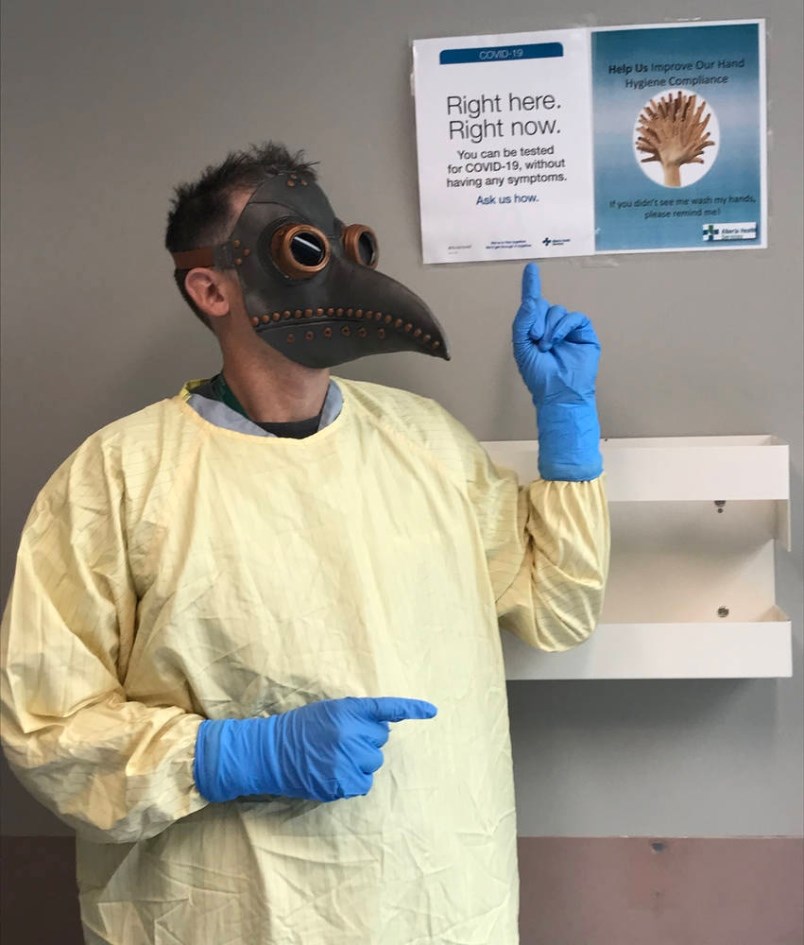

I have a plague-doctor mask that I like. Not really to wear—it creeps people out—but for what it stands for. My mask is symbolic of health-care providers in another era, doing what they could with what they had. It seems relevant today.

Pandemics are not new. Devastating disease outbreaks, spreading across countries, continents and oceans have been with humankind always. After all, “microbes refuse to respect political borders,” according to Yale medical history professor Frank M. Snowden in Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present.

I hear “unprecedented times” at least five times a day. But pandemics are not unprecedented. We are asking the same questions that have plagued people for ages. For that reason, I prefer plague to pandemic, not out of some masochistic desire, but as a nod to our worthy predecessors, and to past similar struggles of our human family.

The similarity between the modern plague of COVID-19 and previous ones is eerie. The furor over chloroquine is a sad repetition of history. Quinine was a hopeful “magic bullet” in the Middle Ages, too. Putting one’s trust in a dubious cure is as old as time.

The only surprising thing is that in modern times, it’s newsworthy: “Man dead from taking chloroquine product after Trump touts drug for coronavirus,” was published by Forbes magazine on March 23.

The plague doctors have received a bad rap for being spooky. Through the dark lens of history, we see them as useless at best, charlatans at worst. But remember, if they were walking around a plague-infested city in their PPE, it was because they hadn’t heeded the common advice to flee to the fresh air. We know that doctors were at the bedside of many of the sick and dying and that they themselves were often victims. If they were in it for gain, they got what they deserved. More likely, compassion and duty were the prime motivations.

Besides death and disability, plagues also bring progress.

“Epidemics … are a major part of the ‘big picture’ of historical change and development,” wrote Snowden. The Middle Ages version changed the relationship between employer and “employee” (peasant, probably closer to slave). With much of the work force dying off, the supply decreased. Labourers could ask for higher wages, and hike over to the next farm if their current paycheque was inadequate.

Plagues foster changes to religious, social and philosophical structures. The exceptionally high death rate among clergy during the European plagues of the 14th through 17th centuries led to both waning authority of the church as well as increased religiosity. A resentment of wealth emerged. Changing philosophies hastened the reformation. You could say that the Black Death brought light to the dark ages.

Will our current plague bring enlightenment? The cliché “it’s too early to tell” is fitting. But the race to produce a vaccine in record time is indicative of some progress. Masking and social distancing aren’t new concepts, but they have found a new adherence, at least in my circles.

Will we see cultural or philosophical changes? Will handshakes disappear, permanently replaced by fist bumps or other salutations at a safer distance? Will masks become permanent accessories? Will I ever be able to wear my plague mask in public without a lot of raised eyebrows, head-shaking or crying babies?

Will our descendants look back at our time and giggle, or shudder in mock horror at our creepy costumes? Will future Halloweeners sport yellow gowns, fake N95s, oversized goggles, and blue nitrile gloves? Will they laugh condescendingly at our debates about aeresolization, fomite transmission and incubation periods? Is there any reason to think that human understanding will not have evolved from here as we have from the past?

But I hope we will remember past plagues to heed conscientious experts and leaders guiding us with sound, though incomplete, science. We scoff at public-health officials, masking/sanitizing/distancing at our own risk.

The rosemary and juniper in the beak of the plague-doctor’s mask may not have warded off evil humours, but transmission was certainly decreased by the covering.

“Often, the attempt [to eradicate outbreaks] failed, but the concepts guiding them still underlie public-health measures to confront microbial assaults,” wrote Snowden.

Will some current practices be similarly unintentionally beneficial? It’s hard to imagine that we don’t know all there is to know, but utterly inconceivable, too. We’re not so different than medieval Europe, “groping towards the future, with one nervous eye always peering over its shoulder toward the past,” as British historian Philip Ziegler put it in The Black Death.

Be safe. Be kind. Be curious.

Jared Bly, an emergency physician at Royal Alexandra Hospital in Edmonton, is pursuing a master’s degree in disaster and emergency management at Royal Roads University.

THe original article appeared here.