A new study published last month by two UBC researchers offers some evidence that mountain biking could be impacting grizzly bears and moose.

But before you think anyone is asking you to get off two wheels, there are a few caveats to that finding, said Cole Burton, assistant professor in UBC’s Faculty of Forestry and co-leader of the Wildlife Coexistence Lab.

“It’s a first publication from a study we’re planning to work on long term,” he said. “We’ll have more to say over time and we don’t want to get ahead of ourselves.”

Alongside lead researcher Robin Naidoo, a research scientist with the World Wildlife Fund and adjunct professor in the Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability at UBC, the study used 61 motion-triggered cameras to monitor wildlife activity in and around South Chilcotin Mountains provincial park for a total of 6,285 nights.

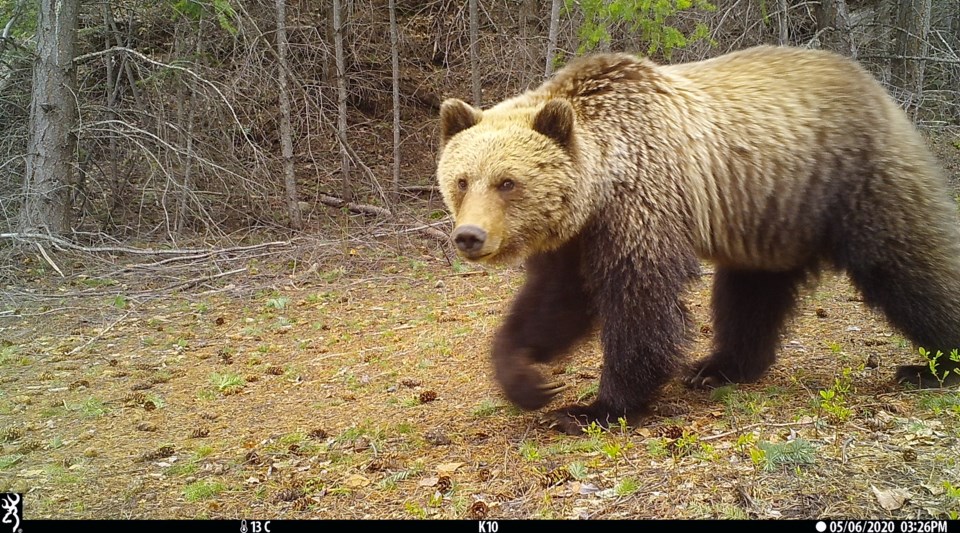

The study, called Relative effect of recreational activities on a temperate wildlife assemblage, focused on 13 species with at least 30 independent detections—ranging from mule deer to red squirrel, wolf, coyotes, dusky grouse, and American martens, to name just a few.

In total, 27 mammals, 32 birds, and one amphibian species were detected. The most frequently spotted animal was the mule deer (4,070 detections).

Human activities, however, were spotted much more frequently than any animals—over twice the number of mule deer.

It appeared that human activity didn’t have a strong negative effect on whether the trails were used by different species—the sole exception being mountain biking. In that case, both grizzly bears and moose were less likely to use the trail after a biker had gone by.

Hiking and horseback riding had the lowest impact.

“At the finer time scale [than one week], all species do seem to be getting displaced from trails,” Burton said. “We’d like to follow up to see if that’s a problem for wildlife or if they’re showing an adaptive response by avoiding conflict.”

In other words, if the displaced species have elevated stress or are prevented from feeding in their habitat, it could be a problem, but researchers simply don’t know enough yet.

They were surprised by the findings that mountain biking had such a strong impact on the two species, though.

“The fact that the amount of impact was comparable to motorized vehicles in our study was surprising,” Burton added. “But we have to interpret it in the context of our study; most of the motorized [vehicles] were outside the park, mountain biking was inside. Animals might be behaving differently in and out of the park. They might be more tolerant of disturbance outside of the park and less tolerant inside.”

The researchers first set out with their study before the pandemic sent throngs of new people into the backcountry this summer. While the goal initially was to look at how humans impact wildlife, and offer concrete data to decision makers like BC Parks, it’s now potentially taken on more value as it continues.

“We felt it was an important topic to begin with, but this has really heightened that in terms of us recognizing the value of what we have in the safety of our home province and how much those recreational activities are important to our livelihood, economy and well-being,” Burton said. “But parks have this challenge: managing for wildlife and nature as well as for recreational opportunity, how they balance those two. They need good evidence to show the trade-offs there.”

Researchers have also used the motion-triggered camera technology from this study and applied it to Joffre Lakes Provincial Park and the Rubble Creek trail to Garibaldi Lake, located in Garibaldi Provincial Park, this summer.

The unusual pandemic restrictions—which closed Joffre up until the present and closed then restricted use to Garibaldi—offered a unique opportunity to researchers, Burton said.

“The pandemic has given us a bit of an opportunity to learn more about the relationship between wildlife and people and parks because of these changes,” he added.

While data on those locations won’t be ready to be released for at least another year, there was one special sighting at Joffre noted already.

“Anecdotally, [we saw] a wolverine at Joffre,” Burton said. “We don’t have anything to compare that to now, but is this a result of less activity in the park? It takes a lot of work to get data on them. One detection on our camera doesn’t mean a whole lot, but it’s tantalizing to think about.”