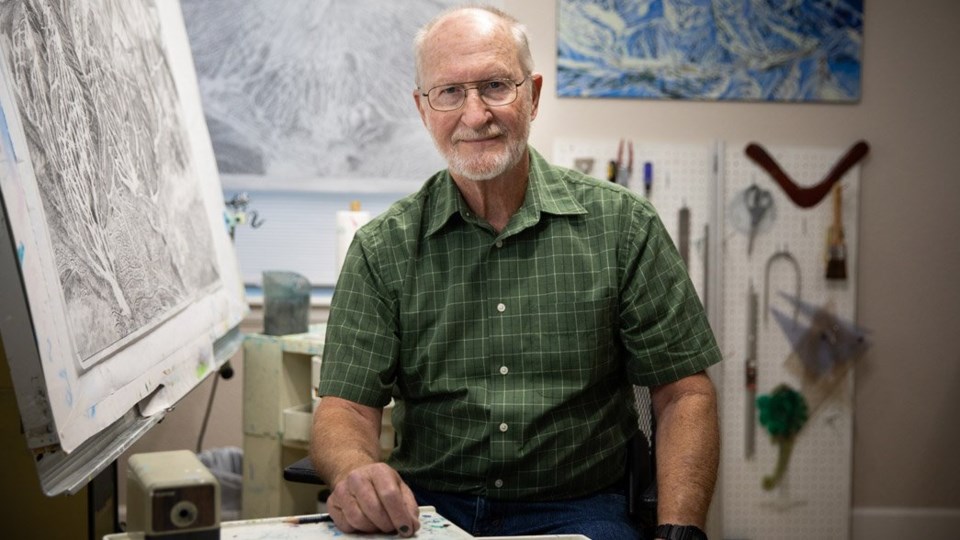

Over the course of a 35-year career hand-painting maps of ski resorts, James Niehues has captured more than 430 maps on five different continents. That’s why, a few years ago at age 70, he realized it was high time to turn some of that functional art into a book.

A $500,000 Kickstarter campaign and a few years later, The Man Behind the Maps: Legendary Ski Artist James Niehues has sold over 50,000 copies around the world.

Pique caught up with Niehues by email to find out more about his technique, why hand painting is better than computer generated when it comes to ski maps, and his first memorable trip to Whistler.

This interview has been condensed for length and clarity.

PIQUE: The promo video on your website sparked a few realizations for me—one being just how long it must take to paint each map! What is the process like? And has it gotten any quicker or easier over the years?

James Niehues: The process is quicker today than in the early ‘90s mostly due to email approvals and digital images. I still compose the mountain with my mind, sketch the scene with pencil, and paint the finished image by hand. So all these things are basically the same, I am just a bit faster due to being so familiar with the process and medium.

By far the greatest challenge is getting all slopes of a complex mountain in one flat representation of the real-life multi-faceted scene. Once the sketch is approved, all the detail must be transferred exactly onto the painting surface. The airbrush is then used to paint the sky and all the snow’s undulating surfaces.

Steeper slopes usually are shaded to set them apart from the easier runs. The tree shadows on the snow are added next. The trees are the most time-consuming part of the painting. I have developed a technique that is creating a tree-like texture then rewetting the colour to blend and adding the highlights and shadows.

You’ve painted so many ski areas around the world, but do you remember painting Whistler Blackcomb? From your list, it looks like you might have done Whistler and Blackcomb when they were owned separately before 1997, then Whistler Blackcomb when it became one company?

JN: Blackcomb Mountain was my first Canadian ski map.

The 1992 project included Blackcomb with insets and a regional view of both mountains for the Visitor’s Bureau. The photo flight was an incredibly dynamic trip from Vancouver. I was really taken back by the beauty of the area as we left the strait, passed Grouse Mountain and headed inland with Garibaldi Provincial Park on our right wing tip.

As slopes of the two mountains came into view, I realized I had quite a job ahead of me! We had gained our altitude to shoot the shots necessary for the regional view, which would go through 10 rolls of film. After some initial high-altitude passes we dropped down to 1,000 ft [305 metres] above the summits to get more shots for the ski maps…then down to 500 ft [152 m] above the summits for detail shots.

We had taken quite a long time getting all the shots and the coffee was coming through. I asked my pilot, a very capable young lady, if there might be a place we could set the plane down before Vancouver, I didn’t think I could make that distance. She was actually happy that I had asked, seems she had the same concern!

She knew of an airfield pretty close and she nosed the plane down. As we approached, a short single runway I noticed there was only a lone hangar, which meant no restroom. We pulled up to the hangar, turned off the engine and I headed to one end of the hangar while she headed to the other.

It’s sure a relief when you’re overdue and been bumping around in the wind currents. I would not drink coffee before photo flights ever again.

In 1993, David Perry called [to proceed] with their trail map [for Whistler Mountain]. I remember his insistence of emphasis on the high alpine bowls. I was honoured that David wrote a perspective to introduce the Canadian portion of my book.

In 1998, I got another call from David Perry. The mountains had merged since the last time I visited and he wanted me to return to paint both mountains as one. During this trip, we used a helicopter for the photo flight. I was a bit better skier this time and skied from the summit to base…off the backside and around into West Bowl. What a great mountain, I wished that I was a better skier. From the air I knew I had only touched a small portion of what Blackcomb and Whistler offered.

What’s it like to finally have so many maps in one book? You had a successful crowd-funding campaign to bring this project to life. What do you think it is about your work that captures people’s attention?

JN: I think my popularity is partly because I’ve been extremely fortunate to have been able to continue painting trail maps through the decades, meaning adults today were kids growing up with my maps pasted on their walls. I painted them as realistically and beautiful as I could to make them images that skiers could dream about.

I had imagined a book by the mid-1990s since I had painted quite a few large resorts by then and felt that by the end of my career I would have quite a collection, which could be put into a coffee table book. [It] seemed like it should do well at all the resorts. The years passed, I didn’t know how to find a publisher and I just didn’t have the time to pursue it. After turning 70, I began to realize if I were to see the book I had so long dreamed about it had better be soon.

It was in 2017 that a fan emailed me and asked if I had a book and if not, he would like to publish it. He was not a publisher. My thoughts were that he had no idea of how much was involved in the process, the layout, production, copyrights, printing, promotion and distribution.

Through the next few months of communication and discussion, I began to have confidence that Todd Bennett had the ability to do what it took to be successful. Within that time, I also got a call from an established New York publisher that was eager to sign me up. We went back and forth between Todd, the avid, enthusiastic skier with no publishing experience, or the [proven] New York publisher.

It was a risk with Todd, assured with the established publisher, but we felt it would be a better book if it were published by a skier with his experience in the skiing community.

I liked how you talk about computer maps vs. hand-painted maps and what you bring to it. How has what you do changed since you first started in the ‘80s? I’m sure no one mentioned computers in the early years!

JN: Certainly a computer is not the best way to portray the great outdoors. The image is a reflection of the office, not of an outdoor experience. When I use a brush, the watercolour comes off the brush in many variations providing better texturing and colour. But the difference comes much earlier in the process. To show all parts of the slopes, I have to manipulate many features in different ways.

I do NOT feel the computer can match the human process of composing the ski map due to the many dissimilar perspectives it takes to portray the mountain and the computer rendering is NOT as realistic as the hand-painting method.

Do you still paint maps or have you done pretty much every ski area out there?

JN: Some years back, I was being interviewed and was asked how I had managed to produce so many ski maps. I was suddenly struck that I had indeed painted several hundred resorts around the world. Not a small task, and I started at the age of 40! I think I am most proud of the fact that I am an example of what is capable if you set your mind to it.

For more, or to buy the book, visit jamesniehues.com/pages/the-man-behind-the-map.